Apochromatic (APO) refractors are widely touted as the “perfect telescope” since they have no chromatic aberration, no obstructions in the light path, and often comes with extremely high-quality optics that provide sharp images with minimal scatter and other issues.

In contrast, what I’ve noticed with achromatic refractors is that they tend to be shafted and largely discounted by many astronomers while also being wildly overrated by others.

The terminology of ‘apochromatic’ and ‘achromatic’ is also wildly unclear, varying depending on who you ask. I believe that its mostly due to the confusion around the nomenclature and biased owners of extremely expensive gear wanting to feel confident that their purchase was a cut above the rest.

- What’s an Apochromat or Achromat anyway?

- Factors Affecting Optical Performance

- Choosing the Right Refractor for Your Needs

- Examples of Achromatic and APO Refractors

What’s an Apochromat or Achromat anyway?

Let’s get the first part out of the way.

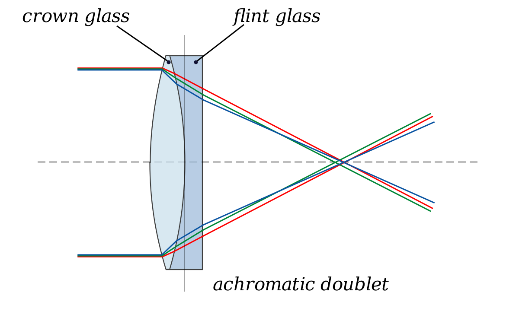

If you plan on doing deep-sky astrophotography using a refracting telescope, you need an apochromatic (APO) refractor. “Apochromat” is an all-encompassing term for anything that is not an achromat. Achromats are simple refractors that use a doublet objective lens made of crown and flint glass without any kind of ED or fluorite glass in the objective.

How Achromats Work

All refractors focus different wavelengths of light at slightly different points, as shown in the diagram above. The stronger the curvature of the lenses (i.e., the larger the scope or lower the focal ratio), the worse this problem gets. This issue is known as chromatic aberration—smeared, out-of-focus halos most easily seen around bright stars, the Moon, and planets.

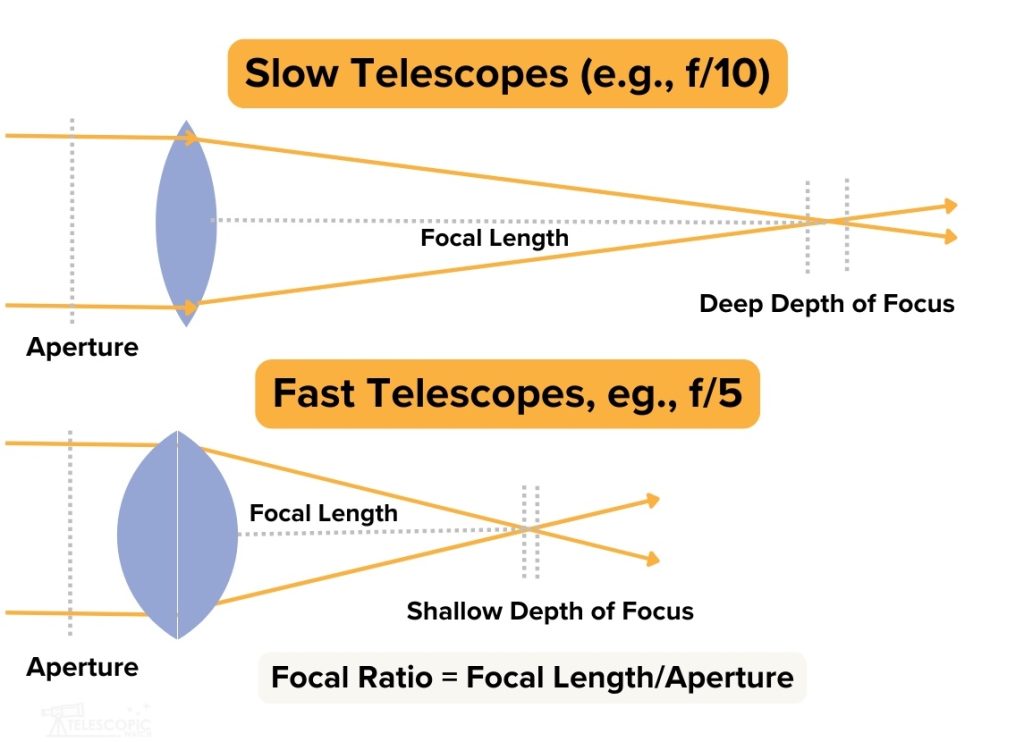

Slow achromats (high focal ratio, e.g., f/10–f/15) are impractical for astroimaging because their long focal length results in a bulky physical size and a narrow field of view. Meanwhile, fast ones (low focal ratio, e.g., f/4–f/7) put up intolerable chromatic aberration.

Controlling chromatic aberration is an uphill battle that refractor optical designs face, and almost any apochromat is going to be better than an achromat for imaging use. I think the real decision challenge lies in what type of apochromat you want and whether you need one for visual observation.

How Apochromats Reduce Chromatic Aberration

Apochromats use extra-low dispersion (ED) glass that has a better refractive index, meaning it focuses different wavelengths of light closer to the same point. This minimizes chromatic aberration and other issues, allowing apochromats to achieve a sharp image suitable for photography and superior for visual use.

These days, the term “apochromats” can refer to a broad range of telescopes, from ED doublets to complex Petzval sextuplet designs. In reality, however, there are essentially three main types of “apochromat”:

- ED doublets use an objective lens with two lens elements just like an achromat, but one of the element uses ED glass in place of the traditional crown or flint glass.

- Triplet Apochromats are usually the most universally referred to as apochromats. They use three elements for the objective lens, with at least one made up of some type of ED glass.

- Petzval refractors are either triplet or doublet scopes with an integrated field flattener/reducer element. They can use a longer f-ratio objective lens to reduce optical aberrations, while the built-in reducer/flattener eliminates issues like spacing, vignetting, e.t.c.. Some Petzvals even allow for the addition of an additional reducer/flattener to make the telescope even shorter in focal length for astrophotography. Petzvals—such as certain older Tele Vue refractors that are no longer sold—used to have non-ED optical design, making them essentially achromats. However, most modern Petzvals are apochromats, i.e., use ED glass.

Beyond these main types, there are also combination of these:

- Quadruplet refractors, which are usually an ED doublet with a 2-element Petzval lens.

- Quintuplet, sextuplet etc. refractors are usually triplets with a Petzval lens, which may have more than two elements.

These terms are still extremely broad, as optical design and arrangement within each category can vary greatly and influence performance as a result. But in general, these three archetypes (as well as achromats) have distinct differences in form factor and performance. This is dictated by a few factors, starting with the type of glass used.

ED glass is rated by its Abbe number, essentially a performance score out of 100. The higher the Abbe number, the lower the chromatic aberration and scatter the glass has. There are a few types of ED glass, all with their own benefits and drawbacks.

“SLD” or “super low dispersion” glass is a term referring to ED glasses with an Abbe number over 90.

Fluorite (Abbe number 95), a naturally occurring mineral, is considered the best type of ED glass. Technically, it’s not glass but crystal.

Pros of fluorite:

- Extremely consistent quality

- Actually, it has even lower scatter than any kind of glass due to molecular structure

- Takes a very smooth polish and cools down to ambient temperatures a little more rapidly

Cons of fluorite:

- Extremely expensive

- If used as the front lens element and not protected, fluorite is rapidly attacked by chemicals in the air. This is worsened by salt, humidity, and pollution. Older fluorite refractors that use it as the front element in a lens have “foggy” lenses which have been essentially corroded, making them the only type of refractors which cannot last indefinitely.

- Due to environmental regulations and cost, fluorite is not as commonly available as it used to be, especially since synthetic ED glass can come very close in performance.

Ohara FPL-53 (Abbe number 94.94) is Ohara Japan’s best attempt to create a glass copy of fluorite.

Similar glasses to the FPL-53 include the Ohara FPL-55 (Abbe number 94.66), a newer version with similar performance to the FPL-53 but slightly better properties for larger lenses and easier properties when worked within the optics shop. Hoya FCD-100 is virtually identical in performance and properties to FPL-53.

Pros of FPL-53 and equivalents:

- Best possible Abbe number other than fluorite

- Fairly common and easily adapted to wide variety of optical designs

- Can take a very good optical figure

Cons of FPL-53:

- It’s not fluorite

- Costs more than cheaper ED glasses

- Expands and contracts more with temperature, requiring greater cool-down time and also increasing difficulty in making a good lens in the shop, which means shoddy FPL-53 lenses can occur and good ones cost more.

Ohara FPL-52 (Abbe number 90) and its equivalent, LZOS OK-4, used to be the best ED glasses available until FPL-53 became available. Today, they are seldom seen, though performance is only slightly worse and other properties are essentially the same.

Ohara FPL-51 (Abbe number 81.54) is commonly used in cheaper apochromats. It is similar to Hoya FCD-1, which is actually slightly superior on paper with an Abbe number of 81.6.

Pros of FPL-51:

- Consistent quality

- Cheaper than FPL-53 or fluorite

- Thermally more stable, requiring less cooldown time in the field and easier to work with to a fine standard of quality

Cons of FPL-51:

- Worse refractive index means it’s harder to design an aberration-free scope

- Almost inevitably produces some chromatic aberration when used without another ED glass, e.g. Explore Scientific FCD-1 triplets, which have blue chromatic aberration on bright targets but otherwise tack-sharp images

- Often, it is misrepresented as FPL-53, usually by omission of clearly stating glass type

CDGM FK-61 (Abbe number 81.6) is supposed to be similar to FPL-51, and is a type of ED glass made in China. It is, on paper, essentially a copy. However, FK-61 glass is not as consistent in quality control as its Japanese counterpart. As such, many telescopes using FK-61 glass may have optical issues stemming from the glass itself, affecting the ability to achieve a fine optical surface or inducing additional scatter.

Other glass is used for the secondary lens element(s) of a refractor where a low Abbe number but good optical quality are needed. Lanthanum and BK7 crown glass are the most commonly used. BK7 is a type of glass vaguely similar to Pyrex (though slightly inferior to mirrors in reflecting telescopes). Schott borosilicate N-BK7 is commonly used. Achromats use flint and crown glass, the latter of which is often BK7.

Other glass types exist. Thorium oxide was used in camera lenses and tank telescope eyepieces through World War II as it provided similar performance to lanthanum glass but was cheaper and easier to produce. Unfortunately, thorium is radioactive, which causes lenses with it to brown/yellow over time, requiring UV light (such as from the Sun) to restore clarity. The radioactivity of the thorium glass is not very dangerous on its own but can ruin film, while long-term use of a thorium eyepiece has been linked to an increased risk of cataracts. Optical parts with thorium glass can be fun curiosities to keep on your desk, but they shouldn’t actually be used.

A wide variety of lens arrangements and optical designs are possible with apochromatic and achromatic refractors, which can have wildly variable performance. It’s important to note that a telescope using any kind of glass can achieve good images, and the correlation of achromats and lower-Abbe glasses with lower performance is purely correlation.

If designed right, an optical engineer can make a good refractor with any available material and number of lens elements, but it may be optimized for different things.

Related Buyers’ Guides

Factors Affecting Optical Performance

All refractors can be good or bad, depending on the manufacturing quality and design optimization.

In terms of optical performance, there are a few things that can be adjusted. In addition to the glass type and the actual curvature of lens elements, spacing of lens elements with an air gap, foil spacers, focal ratio, lens arrangement e.t.c are the tools in the optical designer’s toolkit. Some refractors even use oil in between lens elements, which has its own refractive properties and may improve performance (but of course induces complexity and a potential point of failure).

While a “perfect” apochromat with a fast f/ratio, sharpness both on- and off-axis, minimal scatter, etc. is possible, the reality is that due to cost constraints, most refractors have to be optimized for certain performance attributes over others.

Slower focal ratio refractors are simply easier to design to a high standard of optical performance because the curvature of the objective lens is weaker and the light cone entering the eyepiece/camera is far less steep. However, this, of course, kills the scope’s deep sky astrophotographic aspect (slow focal ratio requires longer exposure time and stabler mount) and limits its achievable field of view for visual use (longer focal length = narrower field of view).

A refractor designed for imaging may sacrifice some sharpness at the center of the field of view in exchange for a sharper, flatter image across the entire field of view—especially at a faster focal ratio. This trade-off is often unnoticeable because the slightly “fat” (less sharp) stars at the very center may not exceed the resolution limit (size of a single pixel) of the camera sensor being used.

Many refractors have field curvature by default and need a flattener to display a sharp image across the field of view of a camera. However, eyepieces induces its own aberrations that may cancel this out. Ironically, this can mean that refractors designed mainly for imaging—whether Petzval or not—can have outright nauseating field curvature when used with an eyepiece.

Since all refractors suffer from at least minor chromatic aberration (reduced to practically nonexistent with the best refractor telescopes), it is going to show up more at certain wavelengths than others. Depending on the purpose of the telescope and/or other design constraints, the wavelengths this falls under can be adjusted, which is extremely important.

Achromats place the extreme ends of the visible spectrum—red and blue—out of focus, creating purple halos. This is in an attempt to control other optical aberrations and works best when the telescope has long enough focal ratio, as then these wavelengths are brought closer to focus. If the out-of-focus wavelengths were concentrated towards one end of the spectrum, a longer f/ratio achromat would’ve still struggled with either red or blue sharpness. Likewise, at low powers with a faster or larger achromat, the red and blue chromatic aberration blur together more than if it were just one color, allowing for images that still appear decent.

The bulk of early apochromats were designed for sharp images at the eyepiece for visual observation and thus are optimized for a fairly even Strehl across the visual spectrum, or to have slight chromatic aberration at each end of the spectrum like an achromat. I observe this to be not true today; most cheaper apochromats are designed for imaging, and given that their market is composed mostly of people who never even look through their telescope, there is little point in optimizing for such.

As a result, many apochromats nowadays have been optimized for performance and higher Strehl towards the bluer end of the spectrum to avoid blue halos around bright stars in astrophotos.

However, in order to cut corners and keep costs down, good imaging performance and sharp stars in these cheaper ED scopes come at the price of severe red chromatic aberration. This may not be noticed in most visual observations or images, but it affects planets, namely Mars and Jupiter, along with some double stars.

I’ve personally witnessd owners of many smaller and less expensive apochromats being surprised at just how bad their views of Mars are in particular, with the planet appearing as a blurry ball while a $100 60-80mm achromat or 100mm tabletop Dobsonian walks all over their prized instrument with clear images of the Red Planet’s dark surface markings and polar ice cap. Ironically, I often had far worse experience in this regard with FPL-53 scopes than with FPL-51 refractors (particularly when the latter are produced at a slower focal ratio).

This is the big one. I know for a fact that high-end manufacturers like Astro-Physics, Stellarvue, and Takahashi polish and figure their lenses to an extremely high standard and will also reject entire glass batches that have the slightest imperfection. This is not true when we buy an ED doublet that costs a few hundred dollars. However, this may just mean a lot of per-unit variation.

Additionally, as previously mentioned, slight sharpness/scatter issues impact visual observation far more than they impact imaging. Deep-sky astrophotographers often get away with surprisingly shoddy optics.

Additionally, slow achromats are easier to manufacture to high standards of quality due to the less exotic properties of the glass used, the minimal number of optical surfaces, and the weak curvatures of the lenses. Thus even cheap mass-manufactured ones can often be surprisingly sharp.

While the above is all true, the current market for telescopes dictates that in general, glass type tends to trend at least somewhat with quality. For example, there are more bad FPL-51 scopes than FPL-53 ones. Also, many achromats are simply manufactured to low quality standards in order to cut costs since their market is primarily budget shoppers anyway. However, plenty of fantastic telescopes with “inferior” ED glass or achromatic optics have been produced.

As such, it’s important to keep in mind that the quality of many refractors does just come down to the optical design and quality control standards for that particular product.

What is the Strehl Ratio?

You might hear the term “Strehl ratio” used in reference to refractors. This is a score for the efficiency of the telescope, i.e., how much light is properly focused and not scattered, put out of focus due to chromatic aberration or defects in the optical figure, etc.

An acceptable telescope has a Strehl ratio of 0.8, while a good one is typically 0.9, and extremely high-end refractors are often Strehl 0.99 or greater. The Strehl ratio can also be used for measuring performance at a certain wavelength of light.

It’s important to note that a telescope with Strehl 0.8 is not literally losing 20% of the light entering it. Instead, it may have some performance issues with one extreme wavelength of light or suffer from defects that only show up at high magnifications, causing image blur without affecting astroimages or low-power views. A lot of fast achromats and cheap ED doublets have Strehl ratios that are quite poor, but they still provide a satisfying experience if you know their limitations.

Choosing the Right Refractor for Your Needs

As refractors are often a compromise in design to achieve their particular goals, their physical attributes can be just as important as the optical. For imaging, selecting what you want comes down to the camera, your mount, your focal length/speed requirements, and your budget.

Refractors for High-Power Visual Observing

If you’re looking for a no-nonsense visual scope for the Moon, planets, and double stars, a fluorite or FPL-51 doublet—usually f/6.5 or slower—is best for most people. A small, slow f/ratio achromat of similar speed can also be great. Fluorite doublets cool down to ambient temperatures the most rapidly, while FPL-51 is fairly close; FPL-53 can take a bit longer. Heavier triplet designs may actually be inferior and take longer to cool down, as well as costing more. Many FPL-53 doublets can also be notoriously bad for planets, as I previously mentioned.

I’d also like to warn you that refractors for visual use are not particularly economical at all. They are luxury telescopes. If you still want one for visual use, shopping for the best-quality achromat or ED doublet possible is wise. You might also want to look at the used market.

Refractors for Deep-Sky Viewing & Imaging

A fast ED doublet or achromat will provide a wider field of view for deep-sky viewing, and the former works for deep sky imaging. Both are terrible for high-resolution planetary and lunar viewing.

Fluorite doublets are ideal for those looking for a lightweight imaging scope with maximum performance, while cheap FPL-53 doublets work great for those getting started with imaging and limited by their budget or mount.

Most slower FPL-53 and FPL-51 doublets or triplets can do double duty for visual use in some form, but work great for imaging smaller targets and will allow you to shoot at a fairly fast f/ratio with a smaller sensor and reducer. But triplets take longer to cool down to ambient temperatures for achieving those sharp images, while weighing a lot more, too.

Petzval refractors are generally best for wide, flat field astrophotography at a fast f/ratio. But I’d consider the huge increase in weight (and cost) is pointless if my camera sensor would be fully illuminated with a cheap doublet and reducer/flattener at the same aperture/focal length specs. They are also limited by their short focal lengths for planetary or high-resolution imaging.

Our OTA rankings page is a good start to your journey.

Examples of Achromatic and APO Refractors

Achromatic Refractor Examples

Budget achromats with good optics sold today include the Explore Scientific FirstLight and Celestron Omni XLT refractors.

Old achromats from Vixen (often sold as Celestron but clearly marked as Japan-made) are particularly prized, as are Swift, Royal Astro, Unitron, and Towa (used to be sold as Meade).

APO Refractor Examples

The best refractors designed for visual observation are arguably the fluorite and other ED scopes from Takahashi, Vixen, and Astro-Physics, along with almost anything from Stellarvue and many of the TEC/LZOS/APM and TMB telescopes. Some of these are discontinued, while others are available.

If you’re shopping new for an apochromat primarily to look through an eyepiece, in addition to the aforementioned premium brands, Explore Scientific’s Essentials 127ED with either FCD-1 or FCD-100 glass is a wonderful telescope for visual use and some astrophotography. The FPL-51 ED doublets sold by Astro-Tech and other rebrands are also great for visual use at a bargain price, albeit so-so for imaging.

Many of the Long Perng refractors and the Sky-Watcher Evostar line are usable for spectacular imaging results as well as great views at the eyepiece.