The Optical Tube

The SarBlue Mak70 is a 70mm (2.75”) f/14.3 Maksutov-Cassegrain telescope with a focal length of 1000mm. That’s right, 1 meter of focal length in a telescope that is only about as big as a large water bottle.

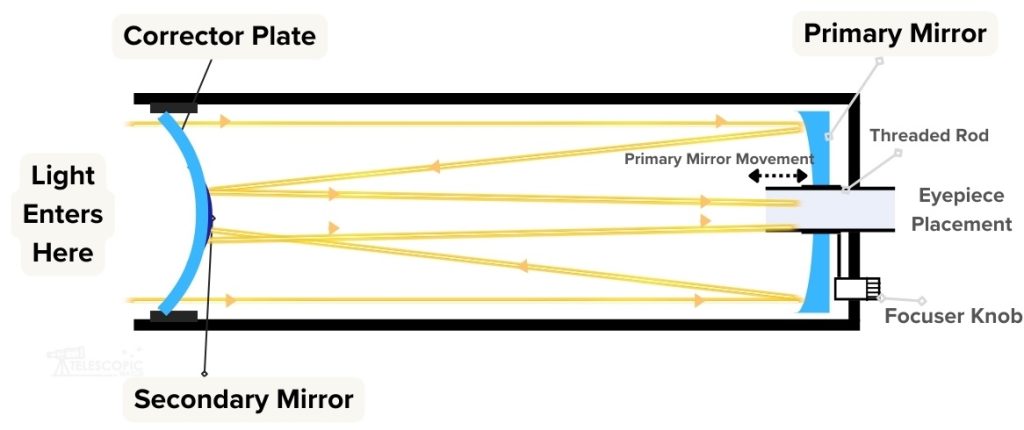

The Maksutov-Cassegrain design “folds” the telescope into an extremely compact tube. It has a front meniscus corrector lens that features an aluminized portion to act as the secondary mirror and a concave spherical primary mirror with a hole in it.

The Mak70, as with most Maksutov-Cassegrain telescopes and other catadioptric designs, focuses by adjusting the primary mirror along a rod, adjusting the spacing of the optics, and moving the focal plane without physically shifting anything attached to the back. There is no “image shift” caused by the mirror wobbling on the rod as you focus, mostly thanks to the diminutive size and weight of the primary mirror.

Maksutov-Cassegrains like the Mak70 shouldn’t need collimation much, if ever, but there are a set of three hex screws behind the primary mirror to adjust collimation should the need arise.

Maksutov-Cassegrain telescopes are known for being sharp optically, and the Mak70 is no exception. Just like the SarBlue Mak60 and many larger Maksutov-Cassegrains, the Mak70 puts up images that would make a Takahashi owner drool. It is subject to a level of optical quality that other mass-manufactured telescope designs simply don’t have, though they win by brute force thanks to their larger apertures, and optical quality can’t compensate for a lack of light-collecting surface area.

Maksutovs aren’t perfect, however.

This telescope’s long focal ratio severely restricts the field of view in addition to the loss of light-collecting power due to numerous optical surfaces and a large secondary mirror. The Mak70’s stupidly long 1000mm focal length boxes in the field of view severely, to just 1.5°—about 3 times the angular diameter of the full moon—with a 32mm Plossl eyepiece or the like. The stock low-power ocular provides a true field of just 1°.

The Mak70’s secondary mirror getting in the way of things, combined with light loss to each air-to-glass surface in this scope, lowers the scope’s light-gathering abilities to be on par with a 60mm refractor. But I can use a nice 60mm apochromat for deep-sky astrophotography or wide-field viewing of nebulae and clusters. The Mak70, I cannot. This is a telescope for the Moon, planets, and double stars; I can’t see much of anything when it comes to deep-sky stuff.

The Sarblue Mak70’s tube and hardware are a mix of metal and plastic parts. Thankfully, unlike many small and cheap telescopes, the Mak70 features a true 1.25” rear port, allowing any 1.25” star diagonal or other accessories to fit in. Its smaller relative, the Mak60, uses a 0.965” port, which vignettes with wide-field 1.25” oculars.

The side of the Mak70’s tube has a metal Vixen-style dovetail with threaded holes, enabling attachment to any astronomical mount, including the provided alt-azimuth unit (likely all you’ll ever need), as well as any photo tripod with a ¼ 20 threaded stud.

Accessories

The Mak70’s rear port accepts any 1.25” accessories, including the provided mirror star diagonal. While cheap and featuring an all-plastic body, the quality control in these mirror diagonals is remarkably good, and there is no appreciable distortion to the image or reduction of optical quality as is commonly seen in cheap mirror diagonals. However, you are free to upgrade to a higher-quality prism diagonal as you please.

For eyepieces, the Mak70 includes 20mm and 10mm 1.25” eyepieces with a polycarbonate plastic body, similar to the included star diagonal. While advertised as Kellners, they are likely designed using the Konig 3-element configuration and boast a little more eye relief than a Kellner or Plossl would at their respective focal lengths. Both eyepieces are fairly sharp, though they lack eyeguards, and offer an apparent field of view of approximately 55 degrees. The 20mm and 10mm yield 50x and 100x, respectively, with the Mak70 telescope.

The 20mm Konig does not max out the achievable field of view in a 1.25” format, and 50x is already a lot for such a tiny scope, so you’re going to want a lower magnification eyepiece, while 100x is about as high as you can realistically use with this telescope. The true field of each eyepiece translates to approximately 1° and 0.5°, respectively—about twice the size of the full Moon for the 20mm and just barely fitting the entire Moon in the field at 100x with the 10mm eyepiece.

A Barlow lens is provided with the Mak70, yielding a 1.5x magnification factor, or 75x with the 20mm and 150x with the 10mm included eyepiece, the latter being realistically beyond what a 70mm aperture is able to handle and still providing a crisp image. This Barlow is built into the provided smartphone adapter. To use it as a Barlow, I had to remove the phone clamp and insert the eyepiece into the holder, then put the Barlow end into the scope’s star diagonal. To use the smartphone adapter without the Barlow, I just unscrewed the lens from the bottom, inserted the eyepiece into the holder, inserted the holder into my diagonal, and attached the top section of the smartphone adapter again. It is admittedly hard to do all of this while still remaining pointed at the target, and the phone inevitably upsets the balance of the scope. But I could still take pleasing images of the Moon and maybe Jupiter with the phone clamp and 20mm eyepiece, either at 50x or with the 1.5x Barlow for 75x magnification.

As for the finder, the Mak70 comes with a 5×24 unit featuring plastic optics and a plastic body. It attaches with a plastic bracket screwed onto the rear port of the Mak70, allowing me to adjust the angle. While these finders are admittedly of low quality, both optically and mechanically, the 5×24 is sufficient for aiming the compact Mak70, and you need not worry about a battery for it, as would be the case with a red dot sight.

What’s more is that the Mak70’s shipping box is carefully tailored to organize the optical tube, tripod, and provided accessories with fairly sturdy and well-decorated cardboard, with constellation art decorating the sides, labeled interior boxes for each component, and even a carry handle. The intent seems to have been that it can be used as a carrying case, and it works remarkably well in that capacity. This is in stark contrast to the mere facade of an attractive-looking exterior of most telescopes’ boxes that I’ve seen, which are rubbish on the inside, nearly impossible to fit back together or close, and usually wind up being thrown out after a few weeks.

Mount

The SarBlue Mak70 uses a relatively rare and remarkable mount configuration for such an inexpensive telescope. It is an alt-azimuth mount that pivots up-down and left-to-right with the telescope attached to the side of the altitude (up/down) axis via a Vixen-style dovetail saddle. The ball bearing mount has tensioning knobs to loosen or tighten the mount’s movements, as well as a pair of easy-to-access slow-motion knobs for control of fine pointing in either direction. As such, it is a remarkably smooth ride for the Mak70. There are no spindly fork tines, no counterweights, no sloppy worm gears, nor the crude and inherently unbalanced motions of a photo tripod pan head with the telescope riding atop and constantly fighting gravity to stay on target. It also attaches to any tripod with a ⅜” stud, such as the extruded aluminum tripod provided.

Those who might have just read the first paragraph and thought of buying the Mak70 just for its mount head alone for their larger Maksutov or a refractor will be sorely disappointed to learn that the mount does not hold up with heavier payloads. With the telescope outboard of the center of rotation and the center of the tripod and no provisions for a counterweight, the whole thing could quite literally tip over with a heavy telescope. And, also, the Vixen-style dovetail saddle is not exactly up to the task of holding a heavy load as it is essentially bent sheet metal. For the Mak70, however, neither of these issues apply.

The mount design is literally the best possible for this scope, especially given the price, and it was tailor-made to fit the Mak70’s needs.

The only issue with the Mak70’s mount in operation is that the slow-motion controls and clutches are not the most well-made. The clutches consist of simple thumb screws, and the slow-motion controls have a lot of backlash when the scope is aimed higher in the sky (particularly on the altitude axis). However, for such a small telescope, these really don’t end up being much of a problem most of the time.

The tripod provided with the SarBlue Mak70 is a simple extruded aluminum unit with legs borrowed from many of the “hobby killer” beginner telescopes and a ⅜” stud atop. The smaller hub used on the Mak70 helps the tripod somewhat with rigidity, as does its stubby and lightweight payload. The legs extend in two sections, and the middle has a center column. The center column cannot actually be retracted all the way without folding the tripod up, as it will slam into the spreader bar and the plastic accessory tray (technically optional) that fits on it. The accessory tray will fit all of the provided kits as long as you avoid bumping it into the center column.

The Mak70’s tripod with the legs extended fully is ideal for a shorter adult or child, while the center column can be raised and lowered depending on where you are aimed in the sky, allowing it to be comfortable for even a fairly tall user while standing, a nice plus if you decide to carry the scope outside on a whim. You do lose some stability with the center column extended further out, but aiming and viewing through the Mak70 is fine with this configuration even at 100x, with only a few seconds needed to quell vibrations.

If you really don’t like the Mak70’s supplied tripod, the ⅜” socket on the mount head fits a lot of things, including my mother’s 1990s Manfrotto Bogen 3126 tripod. I use this tripod with my Mak70 since I don’t bother with accessory trays, and the Bogen has a strap.

Should I buy a used SarBlue Mak70?

The Mak70 is a fairly new product, so worn-down samples are unlikely to be found, and it’s easy to tell if the scope’s front corrector is cracked or the optics are corroded, which would obviate any reason for purchasing. If the price is a reasonable discount from new, there’s nothing wrong with a used Mak70. The only concern is that the accessories (namely the finder or diagonal) could have been cracked or lost, but both are easily replaced.

Comparison: Sarblue Mak70 vs. Sarblue Mak60

A lot of people rightfully ask, what exactly is the difference between the SarBlue Mak60 and Mak70 anyway? That 10mm gain of aperture, after all, is only a 17% increase in resolution, and you only get 36% more light-gathering capability, while both scopes are relatively ineffective for deep-sky viewing anyway.

Most of the improvements of the Mak70 over the Mak60 are not in the optics. The Mak70 has a slightly smaller central obstruction percentage-wise, but not by much, and both scopes are essentially optical perfection. But the Mak70 uses a metal tube rather than a molded plastic shell, and it has a proper 1.25” rear port, so you can insert any diagonal you please and don’t have to worry about vignetting.

The Mak70 also includes a better set of accessories; its mirror diagonal doesn’t choke the light path of the telescope nor cause diffraction spikes like the Mak60’s Amici prism. You get a 10mm Konig and a functional Barlow lens in addition to the 20mm eyepiece, phone adapter, and 5×24 finder.

And, of course, the Mak70 features a freestanding mount and tripod that are actually, well, good. The Mak60’s tabletop Dobsonian mount is fine but obviously limiting in its need for a steady surface. And the lack of fine motions is a bit of a drawback for such a stubby and small telescope—you can’t grab the end of the tube and use it as a lever, really. The two optional tripods for the Mak60 are rather disappointing at best: a cheap plastic photo tripod with no fine adjustments and constant balance issues, and a tiny metal-legged affair that is essentially a glorified display stand.

In essence, the Mak70 is an evolved and improved version of the Mak60 that transforms it from a neat little novelty of a telescope to a bona fide functional instrument. Both serve up sharp and spectacular views, but the Mak70 is a lot more rugged and possesses just a bit more capability than its 60mm counterpart. The portability loss of the Mak70 over the 60 is negligible.

Alternative Recommendations

The SarBlue Mak70 is, of course, a niche telescope designed for the brightest and most detailed objects, namely the Moon, planets, and double stars. With the exception of the smaller Mak60, all of the telescopes listed below rival or beat the Mak70 for lunar and planetary viewing while boasting vastly superior light-collecting power for deep-sky observation.

- The Sky-Watcher Heritage 130P Tabletop Dobsonian features a 130mm primary mirror for superior light-gathering and resolving power compared to smaller 100mm and 114mm reflectors, as well as a more tolerant f/5 focal ratio for easier collimation and less coma. Its provided accessories are quite good, and the collapsible tube helps maximize portability. There is also a bigger Heritage 150P version.

Aftermarket Accessory Recommendations

The SarBlue Mak70 is well-equipped enough with its provided accessories that, combined with its low price, there is only one accessory we would strongly recommend adding: a 32mm Plossl eyepiece for 31x magnification and a whopping 1.7-degree true field of view with the Mak70, the widest it can provide. The 2.25mm exit pupil at this magnification is still tiny, but for those who have trouble looking through the eyepiece, the 32mm Plossl may be your only option for showing children the Moon, for instance, as higher powers make eye placement more tricky and issues like floaters in your eyeball more apparent. The 32mm Plossl is also ideal if you do want to try the relatively futile task of deep-sky observation with this telescope.

A 15mm “redline” or “goldline” eyepiece (67x) may seem a little redundant alongside the Mak70’s bundled 20mm Konig and 1.5x Barlow, but it is considerably sharper than the combination and provides an ideal medium magnification between the 50x of the 20mm and 100x of the 10mm provided eyepieces. However, you may or may not actually need it.

What can you see with the Sarblue Mak70?

The Sarblue Mak70’s relatively small aperture and restricted field of view primarily position it as a lunar and planetary scope. With the 10mm eyepiece, you can effortlessly resolve the phases of Venus and Mercury. The Moon exhibits an abundance of craters, mountains, and ridges, boasting razor-sharp details up to the Mak70’s theoretical upper resolving limits. Mars‘ polar ice caps are visible, and with some luck, you may discern a few dark markings on the planet’s surface when Mars is in close proximity to Earth. Jupiter’s moons are clearly visible even with the 5×24 finder, and the Mak70 has no trouble resolving atmospheric details such as its equatorial cloud belts and the Great Red Spot. The Mak70 is also capable of just barely resolving the disks of the four large Galilean moons surrounding Jupiter, including their shadows during transits.

The Mak70 is, of course, more than capable of displaying Saturn’s rings, and on a stable night, you can observe the Cassini Division within the rings, along with a couple of moons and dull, brown-gray cloud banding on Saturn itself. Uranus and Neptune appear as mere greenish and bluish dots; while Uranus’ disk is technically resolved with 70mm of aperture, it appears as a puffy “star” at best. Neptune, at half the angular size, remains essentially a pinpoint. The moons of Uranus and Neptune, as well as distant and tiny Pluto, are too dim to be seen with the Mak70’s modest aperture; a 6-8” or larger telescope is required for viewing any of these icy worlds.

The Mak70 is ideal for splitting double stars thanks to its sharp optics, lack of diffraction spikes, and lack of chromatic aberration, and there are thousands of colorful pairs that can be enjoyed on a steady evening with the Mak70. Although globular star clusters and planetary nebulae appear as unrecognizable fuzzy balls with a mere 70mm telescope, you can still enjoy views of some bright open star clusters, like M35 or the Pleiades (M45). The Orion Nebula displays the Trapezium star cluster within, along with some of its distinct gaseous structure, while the Lagoon Nebula exhibits a visible glow and a star cluster within. You can also spot some of the brightest galaxies, such as M31, the Andromeda Galaxy. The Mak70 might even unveil M32, the brighter of its two orbiting companion galaxies. However, most galaxies will lack detail or remain invisible outright with a tiny 70mm instrument, especially if any light pollution is present, so it’s important to manage your expectations accordingly. A larger telescope is simply a better tool for the job when it comes to most deep-sky observation.

Mr. Landers gave this neophyte a very objective, very helpful and in depth review that I wish I’d seen this before buying the scope so that I would have had a realistic view of it’s strengths and limitations. I might have decided to wait a bit until I could afford a larger Orion Dobsonian, but then again, maybe not. I live near WKU, which has an active astronomy program and free planetarium shows, so I plan to use this scope more for club events and at home clear evenings (like last night’s crisp and clear sky). I live in the country, with very dark, moderately unobstructed skies. The comparison segment at the end was a nice bonus!