The Moon is the easiest thing to observe with a telescope in the night sky. It’s visible anywhere, even through thin clouds, smoke, light pollution, and haze. You can find and look at it in broad daylight safely, unlike the sun. Aiming at it is trivial even if your telescope lacks a finder or steady mount, and even the smallest and lowest-quality telescope can show you lots of detail. You can observe all of the details on the Moon we describe with a telescope no greater than 4” in aperture, though pretty much any telescope with decent optics and a sturdy mount will do.

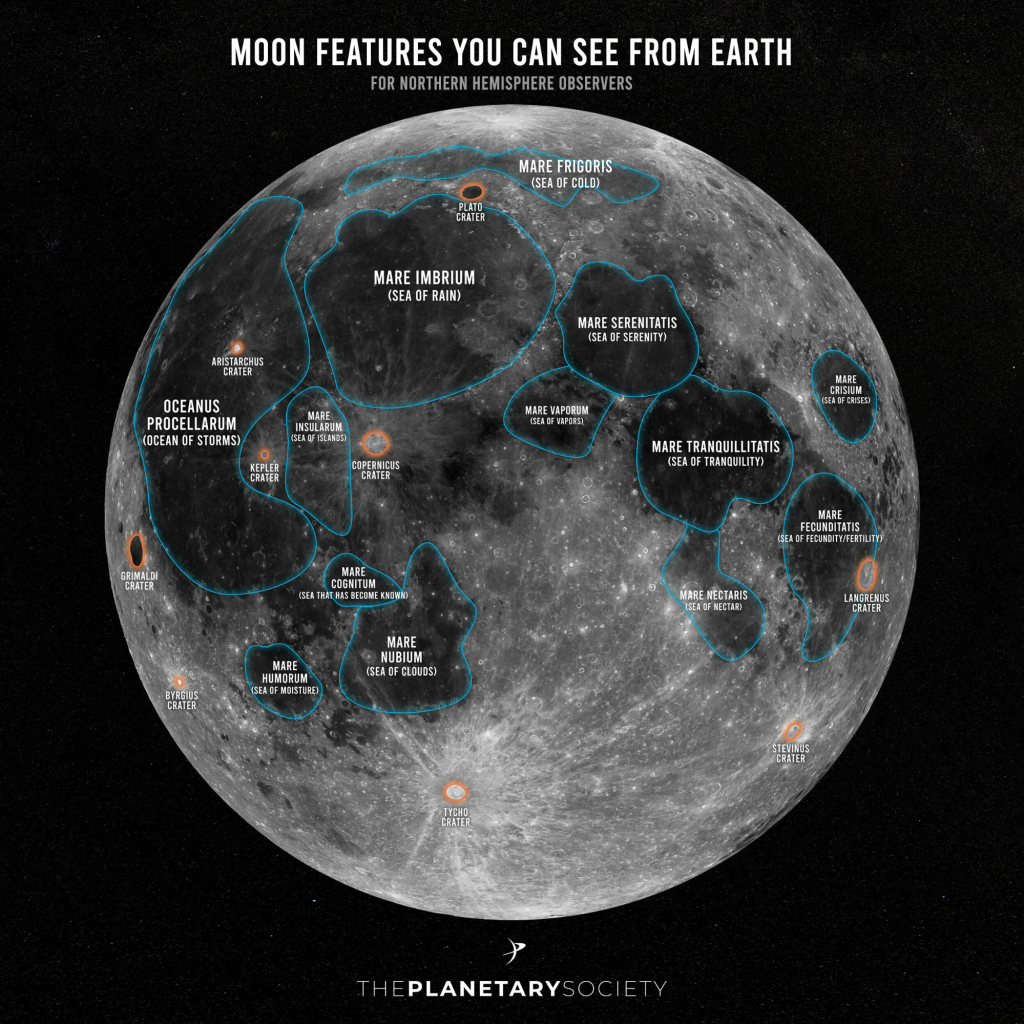

We highly recommend obtaining a digital or print Moon map to aid in your observations of the Moon. Due to the differing and confusing terminology for lunar east and west, combined with the sheer complexity of providing consistent navigation instructions, we aren’t going to be providing location information on lunar features.

When can I see the Moon with My Telescope?

The Moon takes about 27 days to circle the Earth (its orbital period), but due to the Earth’s travel around the Sun, the cycle takes 29.5 days to repeat (the synodic period).

The Moon can be spotted as a very thin crescent within 15 hours on either side of a new Moon by experienced observers, but when it is this thin, it is almost always too low on the horizon in the absence of the Sun – which it is much too close to – to observe well or safely with a telescope. You can observe the Moon for around 24 days or so out of the month easily.

The Moon looks best through a telescope when it is between a thin crescent and a waxing gibbous a couple of days out from the full Moon. During this time, shadows are more elongated, and thus there is more of a sensation of depth. A full Moon is the worst time to observe it. During a full Moon, the Sun is shining obliquely, and thus there is no relief or shadows to be seen on any surface detail, and the Moon is also obnoxiously bright through a telescope (as well as washing out anything else of interest in the sky besides the planets).

When the Moon is seen as a thin crescent with the naked eye, you might be able to distinguish the unlit side from the background sky with the naked eye. This is because the Moon’s “dark” side is lit up with light reflected off the Earth – just like the Moon lights up our planet at night, though a few times brighter on account of the Earth’s greater size and reflectivity. This phenomenon is known as Earthshine and can be seen through a telescope or binoculars during all phases, but not when the Moon is full.

What Size Telescope Do I Need to See the Moon?

Binoculars will show you the largest craters on the Moon, as can any telescope. Telescopes of 3-4” or larger aperture will reveal smaller craterlets, fine detail on mountains, rilles, and ridges, and other details down to just 3 miles (~5 km) in size when atmospheric seeing conditions permit. Larger telescopes are limited by the Earth’s atmosphere most of the time, but in theory, your resolution goes up with a linear increase in aperture – so a 12” telescope can show details around 1 mile across and a monster 24” instrument might have a resolution of 0.5 miles. Linear features like rilles and ridges might only be a few tens of meters wide but can be resolved so long as their length on one axis is above the resolution limit of the telescope due to some oddities with the physics of light and diffraction.

As you might’ve guessed by those numbers, no ground-based telescope has sufficient resolution to reveal the Apollo lunar landing sites – the abandoned Lunar Module descent stages and rovers are only about the size of an ordinary automobile. In the future, if Artemis astronauts were to build large-scale structures like solar power farms or radio dishes, those might be visible as very reflective albeit tiny spots near the lunar South Pole.

Magnification can essentially be thrown at the Moon in unlimited amounts – though exceeding 50x or 60x magnification per inch of aperture with your telescope is going to result in a dim, blurry, and hard-to-focus view, and atmospheric seeing conditions will often limit you to lower powers than what your telescope can handle anyway. Making sure your telescope is collimated and cooled down to ambient temperature is also important for achieving a sharp view.

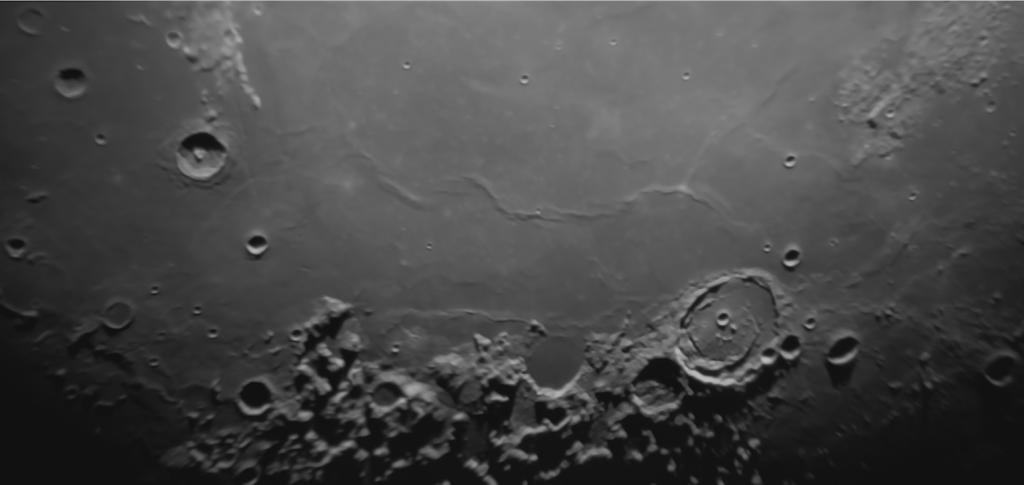

Observing Lunar Surface Features with Telescope

Impact craters are the most common feature on the Moon by far, and you can always see some of interest. This map here shows many areas that can be seen with the naked eye and further explored with a telescope. A proper lunar atlas, much too large to include here, is needed to cross-reference telescopic observations with named features.

Some – particularly younger – craters like Tycho, Copernicus, and Aristarchus, have bright rays of scattered material from the impact, which make them even vaguely distinguishable to the unaided eye. Others, like Petavius or Poseidonius, have rilles within them.

Mare Crisium is a prominent lunar mare that stands out due to its isolation from other similar features. It is visible just days after the new Moon with the naked eye as a near-circular “spot”, has a nearly circular shape, and spans about 555 kilometers in diameter. Through a telescope, Mare Crisium offers a smooth and dark surface, contrasting sharply with the surrounding highlands. The region contains various ridges, rilles, and craters that provide intriguing details for telescopic exploration.

The small craters of Armstrong, Aldrin, & Collins appear near the Apollo 11 landing site, around 50 kilometers away from where Armstrong and Aldrin touched down in 1969.

Schiller is an unusual, elongated crater on the Moon’s surface. Through a telescope, Schiller’s oblong appearance, central ridges, and complex surrounding area make it an intriguing target for lunar observation. Its unique appearance sets it apart from the more common circular craters and adds to the diversity of features that make the Moon a continually engaging object to explore.

The overlapping craters of Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina make a prominent “L” shaped appearance on the waxing crescent Moon. In addition to overlapping craters, craters or “craterlets” within larger craters can be observed, the most famous of these being Clavius, a monster crater measuring 150 miles (232 km) wide and deep enough to fit most of the Rocky Mountains inside. Clavius has dozens of craterlets, which make for a great resolution test for either your telescope or local seeing conditions. The crater Cassini shows two funny-looking round craters within its raised rim, appearing like a face with unequal eyes.

Through a telescope, Montes Apenninus, one of the most striking mountain ranges on the Moon, appears as a jagged and imposing chain of peaks, particularly striking near the terminator, where shadows are elongated. The range is best observed during the first quarter phase of the moon, when it is prominently highlighted.

The tallest lunar mountains are similar to many on Earth, with Mons Huygens at 18,000 ft or 5.5 km, rivaling some of the tallest of our own planet’s summits – though you’d be able to see a lot more from the top owing to the Moon’s lack of an atmosphere and smaller diameter. The Alpine Valley shows prominent graben.

Observing lunar domes, an intriguing geological feature on the Moon’s surface, is a rewarding experience for amateur astronomers with moderate-sized telescopes. The best time to observe these domes is when the sun’s light is striking the lunar surface at a shallow angle, as is the case along the terminator during the lunar sunrise or sunset. The low angle of illumination casts long shadows, emphasizing the contours of the domes and making them more visible.

The Lunar X and Lunar V are fascinating clair-obscur effects that appear on the Moon under specific lighting conditions. The Lunar X is an X-shaped feature created by the interplay of sunlight and shadows on the rims and walls of various craters. Similarly, the Lunar V is a V-shaped pattern. Both appear at the same time and are visible prominently for several hours around the first quarter (or half-illuminated) Moon.

Observing Lunar Eclipses with a telescope

Total solar eclipses are already covered in our separate article and are as much a phenomenon involving the Sun as the Moon. However, they are only one of the two types of eclipses, the other being a lunar eclipse.

Lunar eclipses occur when the Moon passes into the Earth’s shadow, which only happens occasionally as the Moon’s orbit is inclined by a few degrees. During a total lunar eclipse, the Moon initially dims from entering the Earth’s penumbra, where the Earth obscures a portion of the sun as seen from the lunar surface. The Moon then begins to enter the umbra, as the east-facing side gradually appears to have a “bite” taken out of it. Eventually, the whole disk is obscured by the Earth’s shadow. However, our planet’s atmosphere acts like a lens or prism and bends a tiny bit of sunlight around it, illuminating the Moon with dusky refracted sunlight at a fraction of its normal intensity. The scattered light is reddish or orange, like a sunset, due to the refraction by the Earth’s atmosphere. This gives rise to the pop culture “blood moon” we think of when we picture a lunar eclipse.

Depending on weather conditions such as clouds, smoke, and dust near the day-night line on the Earth at the time of the eclipse, the Moon can vary from a bright orange to a nearly invisible gray-brown color. This is evaluated on a scale called the Danjon scale, with 0 indicating a near-invisible brownish eclipsed Moon and 4 indicating an orange-copper eclipse with a bluish-white rim of light around the Moon’s edges. Most eclipses are reddish and fall in the middle range.

Partial lunar eclipses occur when the Moon does not entirely enter the umbra – a recent partial eclipse in 2021 had only a tiny sliver outside the umbra and thus appeared practically total to the eye. Penumbral lunar eclipses can also occur where the Moon either only enters part of the penumbra and barely dims, or the Moon enters the penumbra but little to none enters the umbra.

Lunar eclipses are perfectly safe to observe with telescope, unlike solar eclipses, which require safe filtered eclipse glasses and solar filters. You can use a telescope to watch a lunar eclipse, but the most enjoyable views are really just with binoculars or the unaided eye. Lunar eclipses are incredibly slow, with totality lasting between 30-90 minutes, the umbral phase lasting 30-60 minutes on each side, and the penumbral phase stretching another 30-60 minutes, so they can be up to a 6-hour event in total. Lunar eclipses can be viewed from anywhere on Earth that the Moon is visible, unlike a solar eclipse.

Observing Lunar Conjunctions & Occultations

The Moon frequently occults, or passes in front of, stars. This can be extremely interesting when the star just brushes the edge of the Moon’s north or south pole, and dips periodically behind mountains, crater rims, and other features. This can be used to evaluate detail that is too small or too highly angled to directly resolve from the Earth.

The timing of how long a star takes to disappear behind the Moon can also be used to measure the physical diameter of stars, despite the fact that few can be directly resolved with even the most powerful telescopes. For instance, a star with an angular diameter of 0.001 arc seconds (which would require a telescope over 100 meters across to resolve directly) takes a whopping 1/50 of a second to disappear entirely behind the Moon, which can actually be measured even with analog film. Likewise, extremely close double stars that cannot be split normally can be resolved during an occultation when one star is occulted slightly earlier than the other. For casual observers, seeing a star disappear behind the Moon and reappear later in the night gives a real-time demonstration of just how fast the Moon moves in its orbit and across the sky.

More rarely, the Moon occults all seven of the visible planets in our Solar System as well as appearing in conjunction with them – that is, close by—often enough so that they fit in the same low-power field of view with a telescope or binoculars.

Lunar occultations of stars and planets cannot happen everywhere on Earth at once on account of the Moon appearing in a slightly different part of the sky depending on where you are – an effect known as parallax. This is because the distance between different points on the globe can make up a sizable portion of the distance between us and the Moon – a few percent, yes, but enough to displace it by a few degrees, or several times its apparent width in the sky. Thus, people outside the occultation path will see the planet merely in extremely close conjunction of the planet with the Moon.