It goes without saying, but don’t use your telescope through a window.

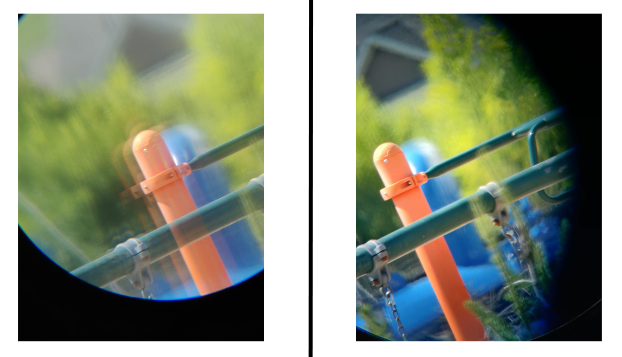

Whether due to chilly temperatures, a desire for convenience, or simply an oversight, I’ve heard of some observers being tempted to aim their telescopes through open doors, screens, or windows. But trust me—the resulting view is going to be barely recognizable and full of aberrations that mar the final image quality.

Only use your telescope outside, preferably well away from any buildings that may radiate troublesome hot air or block your view of the sky, if possible.

What’s Wrong With Indoor Settings?

Every layer of material that light passes through on its way to our eyeball or camera sensor introduces the potential for distortion, reflection, and absorption. This includes air and inert gases, as well as, of course, glass.

A closed window, regardless of how clean and clear it appears, is still a barrier.

Household windows are not designed with optical quality in mind. Most are made of wavy sheet glass, cut immediately after it comes out of the furnace. Unground sheet glass appears bumpy under a microscope, distorting and scattering all of the light hitting it.

Additionally, a window pane might have tiny imperfections, smudges, or even non-stick coatings that can scatter light and reduce the clarity of the image. Some newer windows consist of multiple glass panes with inert argon in between; the separated double layers will cause twice as many optical defects, leading to a poor image.

Even if we decide to observe with our telescope through an open window or door to eliminate the barrier of glass, we’ll be introducing a different problem: air currents.

The inside of our home and the outdoors often have different temperatures. When we open a window or door, these two air masses mix, creating air currents. These currents, though often invisible, can cause turbulence, leading to a shimmering or wavy effect in our telescope’s view—similar to the mirage effect seen on hot roads. This dwarfs the problems from real vision or cooldown issues with our telescope.

A screen—like those found on windows or patios—is made up of a grid of fine mesh. When you aim a telescope through this mesh, the light coming from celestial objects gets distorted, scattered, or diffracted. This results in aberrations or ghost images, making the viewed objects appear hazy or surrounded by diffraction patterns. Even if the mesh seems fine or barely noticeable to the naked eye, it can have a profound effect on the quality of the image through a telescope or binoculars.

Aiming through a window or doorway also restricts our field of view. We’ll be limited to observing only a portion of the sky, missing out on many celestial wonders that might be just out of sight or drift out of our narrow window over the course of the evening.