Finders fall into two major categories: magnified and unmagnified. Each has its advantages, and it is not unusual to have both on larger telescopes.

Using Unmagnified Finders

Unmagnified finders mainly include red dot finders and those that present rings projected onto the sky.

As the name implies, these finders do not magnify anything. In fact, we usually use these with both eyes open so we can see the entire sky as we use the finder to move the telescope to the target location.

- Using Red-dot Finderscope

Red dot finders, or RDFs, are the most popular of the unmagnified finders. You will find them on entry-level scopes and on expensive scopes.

They project a small red dot onto a plastic or glass plate so that it appears to float in the sky. You align that dot with the target and your scope is ready for you to view through the eyepiece. Better RDFs have a variable-intensity dot so that you can dim it down so it does not wash out the target.

- Using Projected Ring Finders

Likely the most popular of this type of finder is the Telrad.

A series of circles are projected onto a screen so they look like they are floating in the sky. The rings represent a known field of view so you can use them to move through the sky in measured amounts.

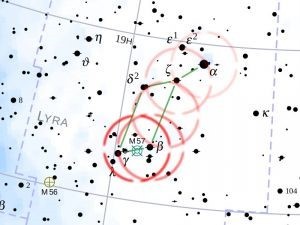

As you can see in the picture, the Telrad projects three circles. The smallest ring is ½ degree. Then we have 2 degree and 4 degree rings.

Telrads can be used in place of red dot finders and offer much greater versatility.

The rings are extremely useful in star hopping, which is a method of finding targets in the sky. If you put a starting point star in the center of the ring, you can identify how far away other stars are that are visible in the Telrad. By moving the rings across the star field by a known amount, you can hop from star to star to find a target.

Telrad finder charts take advantage of these rings. These charts are usually specific to a limited set of targets. The chart shows you where to start and how much to move the scope for each hop as you move the rings across the stars.

You would start in the upper right, which is the bright star Vega. Then you would progress to the next star and the next until you reach the bottom location, which would have the Ring Nebula, M57, which is not visible to the naked eye but would be centered in the Telrad central ring.

Now that you have the telescope in the right location, you go to your low power eyepiece and look around that area. Sure enough, there it is. This method of finding your targets is called star hopping. The Telrad is one of the best tools available for star-hopping.

The Rigel Quikfinder is another example of a projected ring finder. Some people prefer this finder because it is smaller and lighter than the Telrad and will fit in places the Telrad won’t fit.

The Quikfinder projects a ½ degree ring and a 2 degree ring.

- Using Laser Pointer Finders

The laser pointer finder is often based on the same type of hand laser used for presentations. When used at night, the laser pointer projects a line into the sky that can be used to point the telescope.

This is not as precise as a red dot finder or a Telrad, but it is a quick way to point the scope into the general area you want to view.

Laser finders are best used in combination with other finders or telescopes that have a very wide field of view that approaches that of a finderscope. You use the laser for quick positioning and then go to the other finder or a wide-field eyepiece for more precise positioning or star hopping.

I use laser pointers primarily in the warmer months, as the laser does not work very well when it is cold. In the winter, I replace it with a red dot finder.

One thing to take into consideration when using a laser pointer finder is that the projected beam can be seen by aircraft in the area. Doing so is a criminal act in some areas. Many public observing gatherings ban laser pointers for this reason.

If you are going to use a laser pointer finder, be very careful to be sure that there are no aircraft anywhere in the area where you are using the laser. Turn it on only as long as you need to point the scope, then turn it off.

Another reason that lasers may not be welcome at group observing sessions is that it can interfere with astrophotography. The bright laser beam can ruin their exposures.

Take these points into consideration before buying a laser pointer finder device.

Using Magnifying Finderscopes

Magnifying finders are basically small refractor telescopes. Or you can think of them as half of a binocular, as their aperture, magnification, field of view, and specifications more closely resemble binoculars.

Magnifying finders can have straight-through designs, like a handheld spyglass or binoculars. Or they can have diagonals, like a telescope, that bend the light to a more comfortable angle for the user.

The finder on the above telescope is mounted with a standard dovetail shoe. I sometimes swap this finder out for a red dot finder or a laser finder, depending on where I am observing. The magnifying finder works better for me in more light-polluted areas where I can see very few stars with my eyes. I like the red dot finder better when I have darker sky conditions and can see more stars with my eyes.

The orientation of the image in a magnifying finder can vary from device to device. Some will present an inverted image that is also reversed left to right. Some finders are correct up and down but reversed left and right. This is not as strange as it sounds, as there is no up and down or left and right in space. However, if you are using the finder to star hop, it can be a bit confusing at first, but most people get used to it.

Then there are the correct image finders. These usually incorporate some kind of prism, similar to a binocular, which corrects the image so that it is presented correctly up and down and left to right.

Next, we find the right angle finders. These have a diagonal, similar to the diagonal found on most refractor telescopes. This puts the eyepiece of the finder at a 90-degree angle. Depending on what kind of scope you have, this may be very desirable.

For example, Newtonian telescopes have the eyepiece on the side. So a right angle finder would place the finder eyepiece in line with the telescope’s eyepiece. However, if you are using a refractor or catadioptric, where the eyepiece is at the back of the tube, you may find a straight-through finder preferable.

A common designation you should know is the RACI finder. RACI stands for the right-angle correct image.

In the picture, you see the Orion 9X50 RACI finder on my 8” Newtonian telescope. Note how conveniently oriented it is compared to the eyepiece. This allows me to move from finder to eyepiece with ease and without having to get up from my observing chair.

Also note that I have a second finder on this telescope, a laser pointer finder. I use the laser to get into the general area, then move to the 9×50 RACI finder to do my star-hopping or other locating tasks.

While you can add finders directly to your telescope, some would require you to drill holes to add the mounting shoe. If you would prefer not to do that, you can use a dual finder bracket that fits into the shoe that is already on your scope. I use one of these on the Newtonian scope that is shown in the picture above.

I use a laser on this particular scope because a red dot finder would require me to stand or kneel, and bend into an awkward position to see the red dot. But the laser allows me to point the scope without having to bend into difficult positions. I do switch to a red dot finder in the winter when the laser does not work well due to the cold. I also switch to the RDF if I am going to be at a large observing session where the laser might disturb people.

Once finders get past 50 mm in aperture, they are often able to have replaceable eyepieces, just like a regular telescope. In fact, these 60- to 80-mm finders can do double duty when placed on a large telescope that has a long focal length and a narrow field of view.

Having a 70 mm finder with replaceable eyepieces is like having a second telescope that is optimized for low-power wide views. You can use it as your finder or view things just as you would a 70 mm telescope. Its wide field of view will allow you to see things that the larger scope might not be able to fit into its field of view.

My personal experience is that magnifying finders become more important and valuable in light-polluted locations. They allow you to see stars that you cannot see with your eyes alone. Thus, the value of a red dot finder or Telrad type device may be reduced since they can only see what you can see with your naked eye. This is a great time to team up with two types of finders.

Using Finder Eyepieces

This is a low-power eyepiece that maximizes the field of view of your telescope. When used with your other finder(s) this can be a valuable tool when you are looking for hard-to-spot targets. Sometimes your target cannot be seen even with your magnifying finder and you have to go to the eyepiece.

My strategy is to always have an eyepiece that gives me the widest possible field of view for each of my telescopes. For refractors with a 1.25” diagonal, this is usually a 32 mm Plossl. For Newtonian, SCT, and MCT telescopes, this is usually an eyepiece that will provide the lowest power specified by the manufacturer. In this case, you also want the apparent field of view (AFOV) specification eyepiece.

In a telescope with a 2” diagonal/focuser, this will likely be an eyepiece of 32 to 40 mm focal length. In order to maximize the field of view, you will want an apparent field of view in the 65- to 70-degree range.

Naturally, this eyepiece can be used for other purposes than finding. Large targets like the Andromeda Galaxy, the Pleiades, the Hyades, or the North America Nebula are very large, so you would like to have the widest view eyepiece you can when viewing them.