This guide will be about using telescopes for observing Venus—the nearest planet to us and the third brightest object in the sky. When Venus is in the sky, it is brighter than any star besides the Sun.

Like Mercury, Venus is closer to the Sun than Earth is. The result of this is that it is never far from the Sun, from our vantage point. In fact, it never strays more than around 47 degrees away from the Sun.

I’ve seen Venus in broad daylight with my naked eye on exceptionally clear days. Through a telescope, Venus appears like a tiny gibbous or crescent Moon.

When To See Venus In The Sky?

Because of its proximity to the Sun, Venus is highest in the sky during twilight hours, earning it the nickname “Evening Star” when it appears after sunset and “Morning Star” when it shows up before sunrise. I look for a bright, yellowish object that doesn’t twinkle or move—that’s most likely Venus or Jupiter.

Smartphone apps and online tools can help you pinpoint Venus’s exact location from your viewing location. Once you’ve found it, it’s effortless to locate Venus again each night and track its progress.

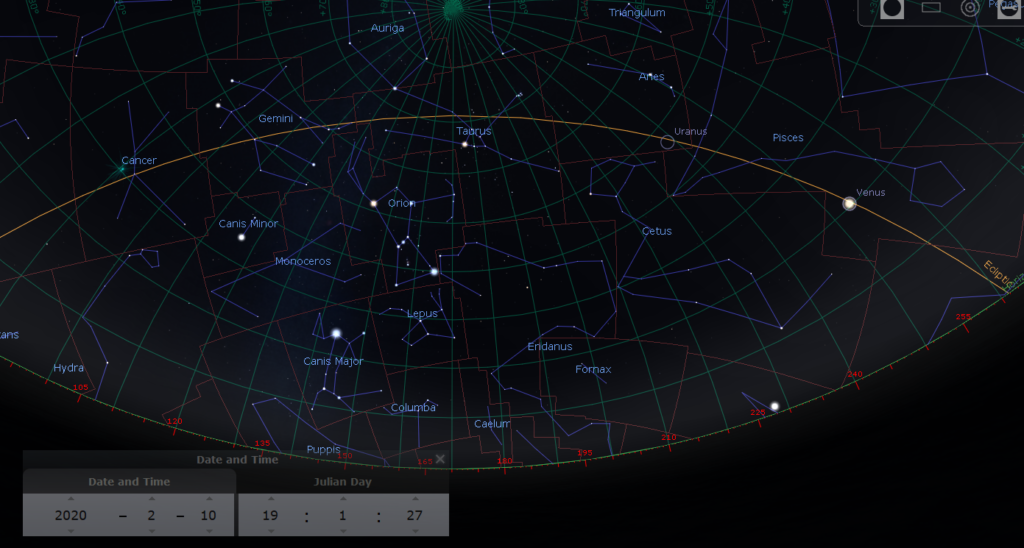

The picture below is a screen capture from the Stellarium, a sky tracking tool. It depicts the sky on February 10, 2020, just as an example, so I can explain how to find Venus.

Notice that the direction we are facing is 180 degrees, or directly South. There is an orange line shown across the image, the ecliptic line. This is the path across the sky traveled by the Sun, moon, and all of the planets. Notice that Venus is shown on the ecliptic.

The ecliptic is always in the southern sky. So, when I’m looking for Venus or any of the planets, I follow the paths traveled by the Sun and Moon to know where to look. Then it’s just a matter of knowing when to look and where to be on the ecliptic to find them.

Elongation & Superior/Inferior Conjunctions of Venus

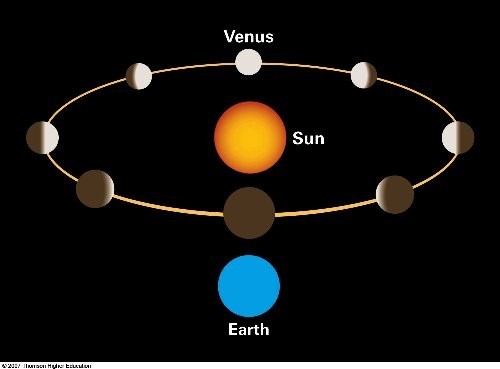

Venus orbits the Sun inside Earth’s orbit, so from our perspective, it rapidly emerges low after sunset, swings out to the east of the Sun in the evening sky, and then dips back towards the Sun, reappearing in the dawn sky to the west. It then swings back around and repeats this cycle every 584 days—its synodic period.

The point at which Venus is at its maximum apparent distance from the Sun in our sky is known as its greatest elongation. At this point, Venus forms the largest angle from the Sun as seen from Earth, appearing farthest from it in the sky—though it does not form a 90° angle in space. The planet appears half-lit when viewed through a telescope, much like a first-quarter or last-quarter Moon.

The dates of greatest elongation are the best times to view Venus, as it spends more time above the horizon before or after the Sun. It appears as a bright “evening star” in the western sky after sunset or a “morning star” in the eastern sky before sunrise. The synodic period is also the time between greatest elongations on each side of the Sun.

Upcoming dates of Greatest Elongation for Venus

- August 14, 2026 (Western elongation)

- January 3, 2027 (Eastern elongation)

- March 21, 2028 (Western elongation)

- October 27, 2029 (Eastern elongation)

- March 18, 2030 (Western elongation)

Upcoming Venus Solar Conjunction Dates

Inferior Conjunction

An inferior conjunction occurs when Venus is aligned between the Earth and the Sun, making it appear as a large, thin crescent when observed from Earth.

- October 24, 2026

- June 1, 2028

- January 6, 2030

Superior Conjunction

Conversely, a superior conjunction occurs when Venus is on the far side of the Sun relative to Earth. Around this time, Venus is not usually visible from Earth due to the Sun’s glare and appears as a small, nearly full disc when it can be seen emerging again in the evening sky.

- January 6, 2026

- August 12, 2027

- March 23, 2029

Finding Venus in the Daytime Sky

Surprisingly, Venus can also be spotted in the daytime sky if you know exactly where to look. The key is good transparency, the same as we’d want for any nighttime astronomical viewing. Dust, clouds, smoke, haze, and other pollutants can brighten and fog up the sky too much to spot the planet amidst a sea of blue. But even on a fairly bad day, it is pretty easy to locate Venus in binoculars or a finder scope.

The best time I try to spot Venus during the day with the naked eye is when it is at its greatest elongation, meaning it is as far from the Sun in the sky as it gets. Of course, taking safety precautions to avoid looking directly at the Sun is vital when you’re looking through a telescope.

I look for a small, bright speck in the sky. Using a Moon or a nearby contrail as a reference makes it easier to locate the planet. Once I’ve seen Venus in daylight, I found myself noticing it again and again if the conditions are good.

If you’ve successfully spotted Venus with the unaided eye, you might also be able to go after Jupiter, which is nearly as big and bright.

What Does Venus Look Like Through a Telescope?

The main thing I see when looking through a telescope at Venus is its phases—similar to those of the Moon.

Venus is covered in dazzlingly bright (but perfectly safe to view) clouds that easily wash out faint surface detail. Usually, these details can only be observed with cameras or by patient observers with filters. The only exception is slight general light-dark contrasts, which I’ve spotted occasionally with even a small telescope. Observing Venus with a telescope in the daytime or equipping a good blue or violet color filter (see the filter section below) may bring out striations in the clouds.

Other than that, the only possible detail you might see is the Ashen Light.

The Ashen Light of Venus is a faint illumination of its dark side observed when Venus is in a crescent phase. It was first reported in 1643 and has been a matter of controversy ever since. Some observers swear by it, while others state they’ve never seen it. The source of Venus’ ashen light is still unknown. Several theories have been proposed, including lightning, airglow, and even auroras, but none have been definitively proven.

Conjunctions & Occultations of Venus

Due to its position in the Solar System as an inner planet, Venus frequently appears in conjunction with other planets in the night sky, mainly due to its proximity to the ecliptic plane. Occasionally, these are close conjunctions where both Venus and another planet will fit in the same telescopic field of view.

The next interesting conjunction I’m looking forward to is on August 12, 2025, when Venus approaches to within about 1 degree of Jupiter in the morning sky.

Venus also partakes in lunar occultations and conjunctions quite frequently, where the planet appears very close to our Moon or is blocked by it altogether in an occultation. These events are always a treat to observe due to Venus’ bright and shining presence in the sky along with the phases of both participants.

One particularly close approach between the two occurs on September 14, 2026, resulting in an occultation for some observers.

Transits of Venus

One of the rarest predictable astronomical phenomena is the transit of Venus. This event occurs when Venus, from our perspective on Earth, passes directly across the face of the Sun, appearing as a small black disc moving across the Sun’s bright surface.

The plane of Venus’ orbit is 3.4 degrees off from Earth’s plane of orbit so these transits of Venus across the face of the Sun happen very rarely.

These transits occur in pairs eight years apart, separated by long intervals of over a century. The last pair of transits occurred in 2004 and 2012, which was a huge event within the astronomy community. Unfortunately, I will not be around to see the next pair which will occur in 2117 and 2125.

Historically, these transits have been important in measuring the scale of the Solar System as well as studying Venus itself.

Telescope Color Filters for Observing Venus

Color filters for telescopes can be helpful in enhancing our view of the planets, and this is particularly true when observing Venus, a notoriously tricky planet to study due to its intensely bright, featureless appearance. The use of color filters can help improve contrast and bring out subtle details that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Normally I don’t recommend color filters very strongly, especially cheap ones that just blur my view. They are generally only useful in fringe cases. But if I really want to see Venusian cloud structure, I find a filter to be one of the more effective ways to improve my luck.

One of the best, but less widely available, filters for observing Venus is the #47 Wratten “Violet” filter. This is a dark blue filter that is known to bring out the most subtle features in Venus’s cloud cover by increasing the contrast. However, this filter tends to dim the view quite significantly. Therefore, I’d only use it with larger telescopes, typically those with an aperture of 8 inches or more.

For smaller telescopes, the dimming effect of the #47 Wratten filter is too great, and so, I think a #80A filter is probably best.

The #80A filter, which is widely considered the best available for Jupiter and fairly common, is another option when observing Venus. This blue filter can help to slightly increase contrast and reduce the planet’s dazzling glare, although I find its effects to be generally less pronounced than the #47 Wratten filter.

I’ve tried other filters, such as the #21 (orange) and #38A (dark blue), which can sometimes enhance the view of Venus. But I’ve noticed that their effectiveness tends to vary and a #47 or #80A filter is probably more useful. The #21 Orange is commonly used for lunar observation in the daytime to reduce the blue filter of the sky, but the bluish tint of the daytime sky actually helps increase contrast on Venus, so I only give this filter a try when the Sun is well below the horizon.

Neutral density filters and other color filters are largely ineffective when observing Venus. Neutral density filters simply reduce the amount of light entering the telescope without altering the colors, which, while perhaps more comfortable to some, doesn’t contribute to bringing out any additional detail in Venus’ cloud tops for me.

Other color filters might have beneficial effects, but none have been shown to consistently enhance the view of Venus like the filters mentioned above.

Imaging Venus’ Surface in the Infrared

Venus emits a lot of heat because of its thick atmosphere and its proximity to the Sun, and this heat can be detected by spacecraft and telescopes with thermal imaging capabilities. Infrared light is invisible to the human eye, but it can be detected by special cameras. However, in addition to the cost of the equipment, setting up for this type of imaging can be difficult. For starters, you’ll need a camera and filters to shoot around the 1 micron (1000nm) range.

The atmosphere of Venus is very bright in the thermal/IR spectrum, and it can make it hard to see faint features on the nighttime surface of the planet. The entire daylight side will need to be overexposed. The rather long exposure time of your images also limits the ability to compensate for bad atmospheric conditions with stacking, so you need to start out with fairly good seeing conditions. Venus should be as high in the sky as possible and in a crescent phase, and you should be equipped with a fairly large telescope—10” or bigger is best.

where can i get a 35mm camera and lens to take pictures of planets and orion

Camera store Amazon Lots of places.

If you are asking about a 35 mm film camera, well those are likely pretty rare these days but I would still suggest a camera store.