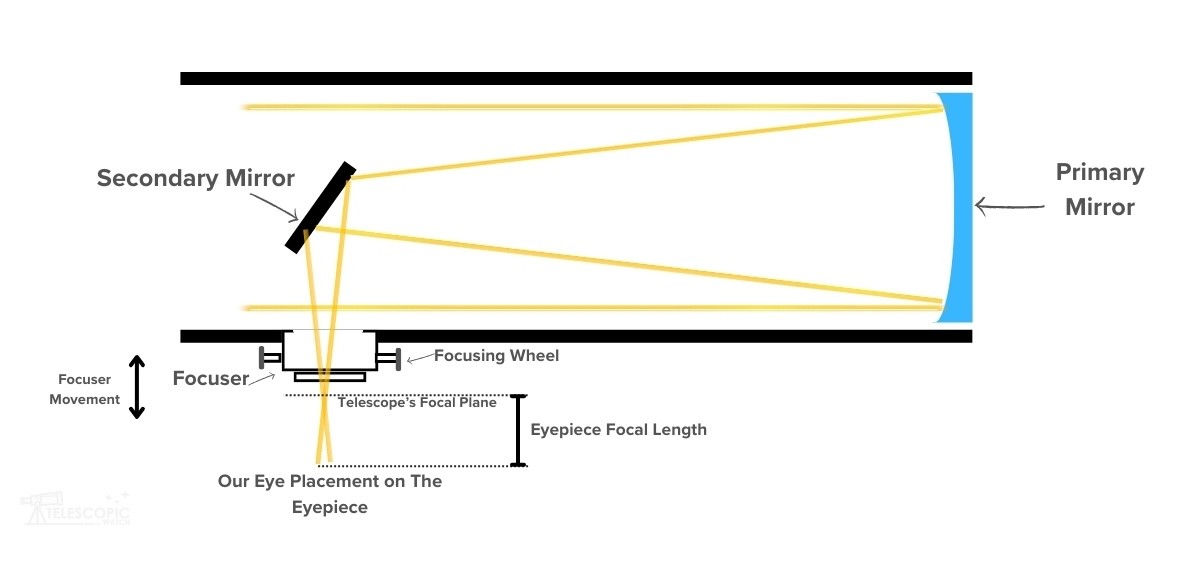

Focus in a telescope is achieved when light rays from a distant object, such as a star or planet, are converged (brought together) at a single point by the telescope’s lens or mirror. When this convergence point coincides perfectly with the focal plane of our eyepiece or camera sensor, the object appears sharp and clear. Focusers help with this by sliding the eyepiece back and forth, effectively moving the focal plane of the eyepiece along with it.

Focusers themselves are a component of every telescope, but they’re often viewed as a bit of an afterthought. This is partly because most focusers work “well enough” that little is thought of them beyond fulfilling their basic job.

Focusers are, however, just as essential and precise a part of your telescope as any other mechanical component and arguably nearly as much so as the optics.

A bad focuser always results in poor high-magnification performance and considerable frustration for me. With heavy loads like premium eyepieces or a camera setup, a low-quality focuser may sag or wiggle enough to be a genuine danger to your equipment.

What is a Focuser?

At its core, a focuser is an adjustable holder used to attach an eyepiece, camera, or other accessories or adapters to a telescope.

Almost all telescopes come with either a built-in focuser (on most mass-manufactured catadioptric telescopes) or an attached external focuser (on most refractors and reflectors).

Telescopes with an external focuser may be able to have their focuser swapped out for a different one, though new holes may need to be drilled if the screw patterns aren’t the same between the new and old focuser units.

A typical external focuser works by moving the eyepiece or camera in and out along the telescope’s optical axis. This movement alters the distance between the eyepiece and the telescope’s primary lens or mirror, which in turn changes the point where light rays converge to form an image. In the case of most built-in focusers, it is the primary mirror itself that moves to achieve the same result.

Some focusers can even be motorized and controlled remotely to achieve precise focus without touching the telescope, thereby minimizing vibrations and ensuring precision adjustments for astrophotography (though generally unnecessary for visual work).

Focuser Size Formats

Telescope focusers come in various sizes, primarily determined by the diameter of the eyepieces (or other hardware) they can accommodate. The most common sizes are 0.965-inch, 1.25-inch, and 2-inch, with occasional larger sizes available for astrophotography or other specialized purposes.

- 0.965-inch Focusers: This is an older standard, often found on vintage or very basic telescopes. Eyepieces of this size are typically of lower quality and offer a narrower field of view. I rarely see this size in modern astronomy equipment.

- 1.25-inch Focusers: This is now the most common standard in amateur astronomy. The 1.25-inch focusers and eyepieces strike a good balance between field of view, quality, and cost. Many telescopes only take 1.25” eyepieces due to physical limitations or a lack of need to go larger.

- 2-inch Focuser: Used by more advanced and larger telescopes, 2-inch focusers allow for eyepieces that provide a wider field of view, which is particularly beneficial for deep-sky observing. A 2” focuser is also necessary for deep-sky astrophotography with many common camera sensor sizes, as well as to utilize accessories like focal reducers, field flatteners, and coma correctors, which we need to employ for this task.

- Special Large Formats: Larger formats, such as 2.5-inch, 3-inch, or even larger, are typically used in professional or highly specialized amateur telescopes. These allow for even wider fields of view and can accommodate heavy-duty accessories, but they are generally overkill for most amateur applications.

Types of Focusers

With the exception of the internal focusers used on catadioptrics, telescopes today typically have one of three types of focusers: helical, rack-and-pinion, or Crayford.

All do the same thing: move the eyepiece/camera and other relevant accessories back and forth relative to where the telescope’s objective lens or mirror focus the light.

In its most basic form, a focuser can be a tube in which the eyepiece slides back and forth or a draw tube holding an eyepiece that slides back and forth inside a larger receptacle. I still occasionally see some very old or homemade scopes using this system. In any telescope with a focal ratio faster than about f/10, it is extremely difficult for me to focus precisely at high magnifications with such a device; I cannot use heavy eyepieces, and leaning on the eyepiece too hard pushes it inward.

All in all, a proper focuser is certainly worth the trouble of implementing on any telescope.

Focuser Adapters & Clamping Mechanisms

There are two main ways most focusers employ for clamping an eyepiece.

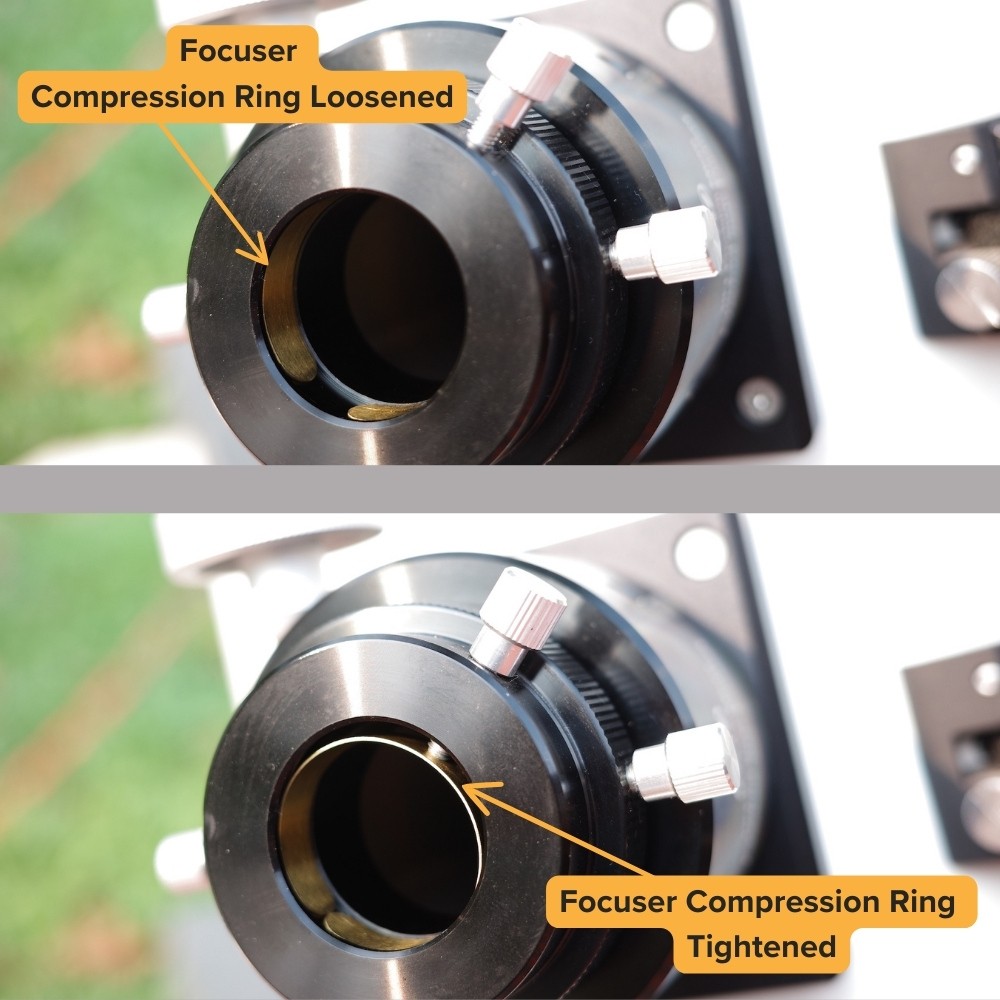

- Compression Ring: This method uses a brass ring that applies even pressure around the eyepiece when an external screw is tightened, offering a secure grip without marring the surface of the eyepiece barrel. I generally prefer to use this with my higher-quality eyepieces, as it minimizes the risk of scratches and provides a more stable hold. The “rotating lock” and “ClickLock” adapters sold by companies like Baader I’ve seen are more or less just variations on this same design, but with a twist-lock rather than a thumbscrew tightening mechanism.

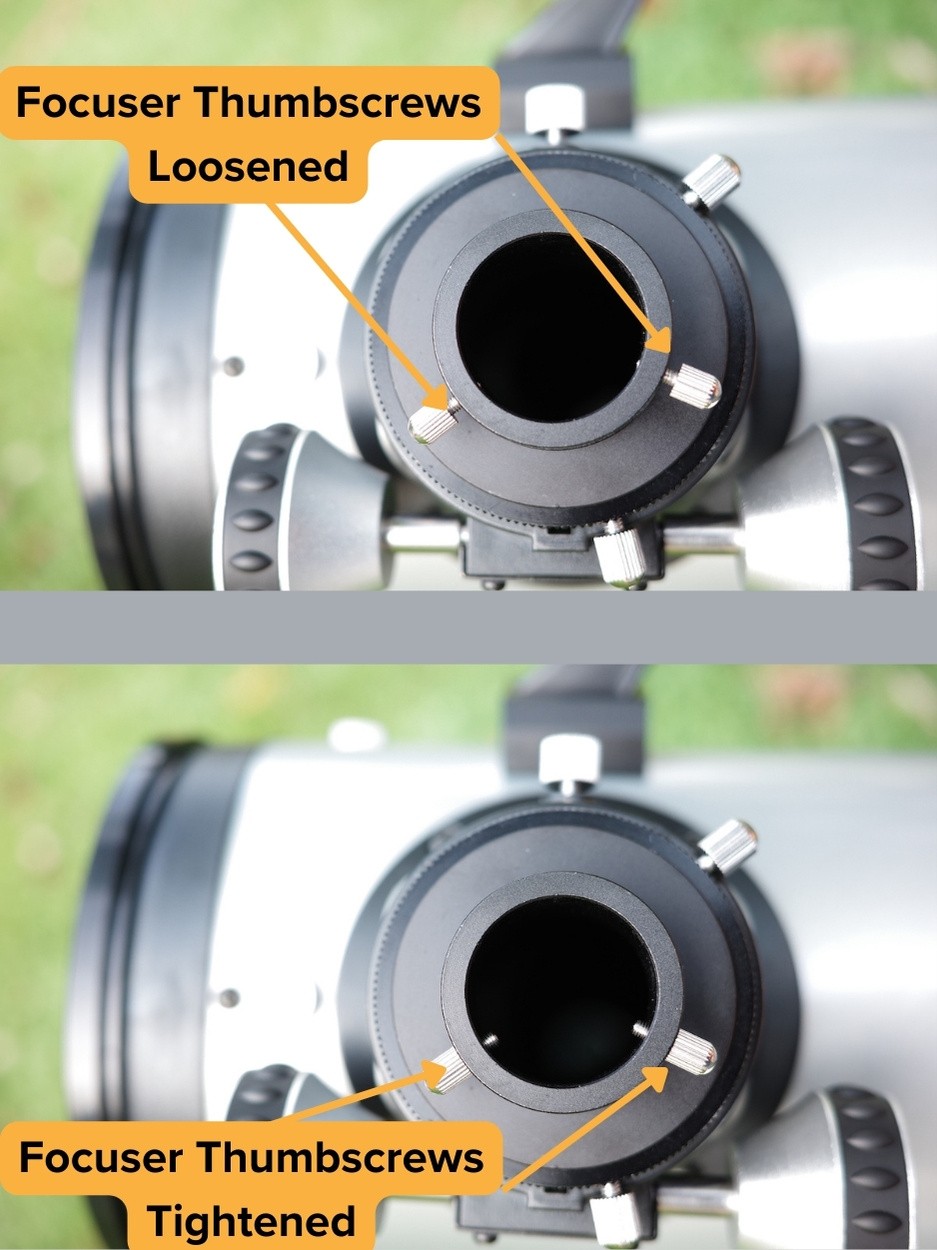

- Thumbscrew: This is a more straightforward method, where one or more screws are tightened directly against the eyepiece barrel to hold it in place. While effective, this can sometimes damage the eyepiece’s finish and doesn’t provide as secure a grip as a compression ring, especially for heavier accessories.

Many older telescopes don’t have a proper thumbscrew adapter. Instead, they grip the eyepiece with a slotted metal flange made of soft brass or aluminum—or even just a 1.25” chrome pipe flange. Some eyepieces, such as the Tele-Vue Ethos series, still have an external thumbscrew to clamp onto these kinds of 1.25” flanges securely. This is fine with lightweight eyepieces but poses a problem with today’s heavy, ultra-wide oculars. In those cases, I often swap out the offending eyepiece holder or add a hose clamp around it to tighten the grip.

Installing a New Focuser on Telescopes

We can retrofit a new focuser onto most refracting or reflecting telescopes fairly easily, which is why I’ve taken the trouble to make recommendations for some aftermarket focusers in this article.

- On Refractors

Refractors usually require me to buy or make an adapter flange to fit the new focuser body onto the back of the tube. Installation is as easy as dropping in the replacement flange after removing the old focuser, usually with just a screwdriver.

- On Reflectors

If the new focuser and old focuser body do not have the same screw hole pattern, installing a new focuser on a Newtonian reflector requires me to drill a few additional holes in the tube.

This means I’ll want to first remove the spider holding the secondary mirror and the primary mirror cell if I’m doing this on one of my solid-tubed telescopes that doesn’t come apart further. Any drill with hard metal bits makes short work of the thin-walled metal, plastic, plywood, or cardboard tube walls.

However, enlarging the actual hole in a tube for a wider focuser drawtube is a different story. I often require a Dremel or some other small cutting tool to do it while making sure that the focuser would still be centered over the secondary mirror.

- On Catadioptric Telescopes

The external focusers that screw onto the back of catadioptric telescopes need no explanation as to how they are installed.

Starlight Instruments sells a Feather Touch planetary gear knob for many Schmidt-Cassegrain and Maksutov-Cassegrain models. Installing it required me to remove the old focuser knob and bearing assembly with a screwdriver and hex keys, but it was still a fairly straightforward process.

My Telescope Focuser Recommendations

I Got The Best Quality from Starlight Instruments 2” Feather Touch

The Best Value Focuser I’ve Owned is GSO’s 2″ Dual-Speed Crayford

Dual-Speed Focuser Knobs

Many focusers offer dual-speed adjustment, which is a setup where a second small knob, affixed to one of the main focuser knobs, operates on a different gear ratio—typically 1:10. Meaning that for every ten rotations of the smaller knob, the larger knob (and thus the focuser) rotates only once. This setup provides a finer degree of control.

This system keeps the design compact while allowing smooth, precise adjustments by translating a lot of hand movement into very fine focuser movement. I always find a dual-speed focuser really versatile, letting me quickly switch between coarse and fine focusing. It’s especially helpful during dynamic observing sessions where I need to jump back and forth between rough adjustments and fine-tuning.

Schmidt- and Maksutov-Cassegrains can also be adapted to have dual-speed focusers, though the use of such a system by the manufacturer is rare (a few scopes, such as the Maksutovs offered by iOptron, do have a dual-speed knob by default). Starlight Instruments does sell Feather Touch dual-speed knobs for many commercial catadioptrics, however. A dual-speed knob from them is expensive but certainly worth it if you do a lot of high-magnification observing or planetary imaging, like I do.

Great article! Me being an amateur astronomer I realize how important focus is on any telescope. I recently purchased a 6 SCT and found it to be very difficult to get sharp focus on the planets while trying to focus with my 2.5x tele vue powermate. So I invested in a auto focuser I really hope this will solve my issue. I like the hands off approach to focusing. The less you touch your telescope the better off you will be.

Thank you for your insight on focusers i am going to up grade my meade 8 inch Newtonian