The first time I saw Saturn and those beautiful rings in a telescope eyepiece, I had a WOW moment. When I’m showing the sky to friends, if Saturn is in the sky, I’d always start with Saturn.

Just to give you a quick intro: Saturn is the second-largest planet in the solar system after Jupiter. From Earth, Saturn is the third planet out—after Mars and Jupiter.

How & When to Find Saturn in the Night Sky

I’ve been able to see Saturn with the naked eye, even in very light-polluted locations. It is about as bright as the brightest stars.

Saturn is fairly easy to find when it is in the night sky. It travels along the ecliptic plane, an imaginary line that extends from east to west across the southern sky. This is the same path that the Sun, Moon, and planets travel. So, note the paths of the Sun and Moon, then look for Saturn to be traveling along that same path. For most of the year, Saturn can be seen in the night sky, although its specific location varies depending on the time of year.

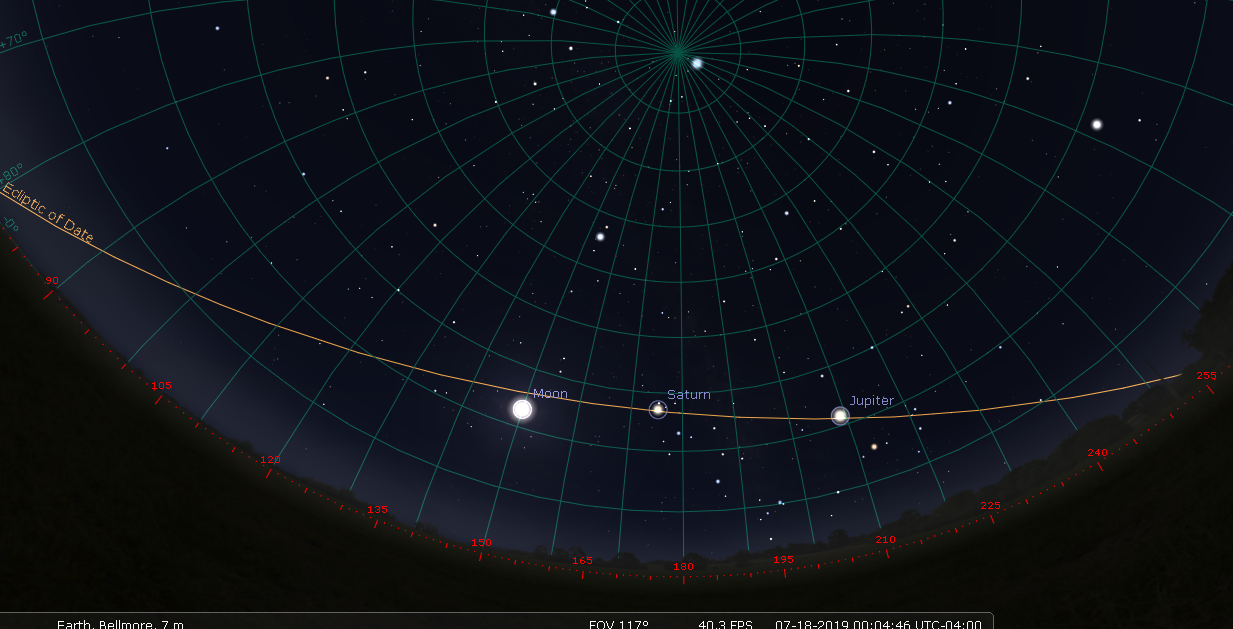

The picture below is a screen capture from the planetarium program Stellarium with the observer facing directly south, 180 degrees on the compass. As you can see, the ecliptic line is marked in orange. We see the Moon, Saturn, and Jupiter traveling along the ecliptic path.

Remember, Saturn is not always in the night sky and is not always visible from Earth. A quick internet search will reveal lots of programs, phone apps, and websites that will let you know when Saturn will be visible. Or you can use a planetarium program, like Stellarium, to view the changes in the sky to see when Saturn will be visible.

One of the best times to see Saturn is during the weeks and days around its opposition—when Earth is positioned directly between Saturn and the Sun. During opposition, Saturn is closest to Earth, making it appear brighter and larger. It also rises at sunset, reaches its highest point in the sky around midnight, and then sets at sunrise. This means that it’s visible all night long.

Oppositions of Saturn occur roughly once every year—every 378 days, to be more precise.

The next opposition of Saturn occurs on September 20, 2025. It will remain visible in the evening sky after sunset for several months afterwards until it sinks into the glow of the Sun, reaching superior conjunction (its furthest away, on the opposite side of the Sun) on March 25, 2026, and re-emerging in the pre-dawn sky sometime in late April. Saturn will reach opposition again on October 4, 2026.

Transparency, Seeing, and the Secret to Sharp Saturn Views

I always try to view Saturn when it is high in the sky. At this time I’m looking through the least amount of Earth’s atmosphere. Air pollution, dust, smoke, and moisture in the atmosphere scatter the light coming from Saturn—factors that all affect what we call transparency.

In addition, the Earth’s atmosphere is always turbulent, which causes Saturn to drift in and out of focus. Think in terms of looking through a glass teapot of boiling water and trying to read a book that is located on the other side. We describe the degree to which turbulence is impacting our image of Saturn as “seeing” conditions. Good sight means the air is less turbulent. Bad seeing means it is very turbulent, causing Saturn to drift in and out of focus.

Seeing and transparency conditions can vary greatly from day to day and hour to hour. So, if the view was great last week and poor tonight, the issue may be the atmosphere, not your telescope.

Local seeing can also be a factor. If I’m viewing across a road, houses or commercial buildings, the releasing heat as they cool in the evening can cause heat shimmers, impacting my view. As the evening goes on and these structures cool, the shimmering heat diminishes. As a result, we may get better views in the evening or early morning.

Magnifications to See Saturn

Even when I’m using a typical handheld 10X50 binoculars, I can tell that Saturn is not a star as it appears to have a sort of oval shape. While this isn’t enough magnification to see the rings, it is enough to confirm that I’m looking at Saturn and not a star.

I begin to see the rings of Saturn with as little as 20-30x magnification. However, to get a clear view of the separation of the rings from the planet, I require higher magnification.

I typically view Saturn—and all the planets, really—at higher powers such as over 100X and, depending on conditions and the telescope I’m using, over 200X. The greater the telescope’s aperture and the better the atmospheric conditions, the higher the magnification I can apply. But I’ve learned to use good judgment, as more magnification might give me a larger image, but I may also lose quality and detail.

What Features to Look For

- Rings’ Shadow On Saturn

One of the most spectacular sights I see when observing Saturn is the shadow the planet casts on its rings. This feature is relatively easy to spot, even with a small telescope.

The visibility of the shadow varies with Saturn’s season, which is determined by the tilt of the planet’s axis and its position in its 29.5-year orbit around the Sun. When Saturn is near its equinox, the rings are edge-on to the Sun, and the planet’s shadow on the rings is a thin line just along the rings. Near Saturn’s solstice, the shadow extends across the rings, creating a dark wedge that I can easily observe.

The shadow adds a stunning three-dimensional quality to views of Saturn and serves to highlight the planet’s complex ring system.

- The Cassini Division

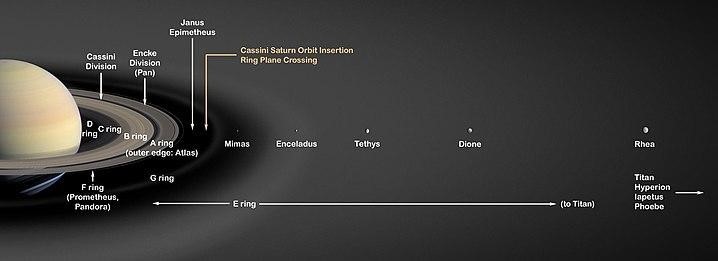

The Cassini Division is one of the most remarkable features of Saturn’s ring system that we can observe from Earth. Named after the Italian-French astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, who discovered it in the 17th century, the Cassini Division is a gap approximately 4,800 kilometers wide between the A Ring and B Ring.

Despite being called a ‘division,’ it’s not empty but contains a much lower density of ice particles compared to the adjacent rings.

When the rings are at their maximum tilt from Earth, even a 3” (76mm) telescope has shown me Saturn’s Cassini Division. Since we had a ring plane crossing recently in March 2025, the Cassini Division now requires a considerably larger (4” or greater) instrument and above-average conditions to be resolved easily. By 2026, it’ll be much more noticeable through telescopes, with peak visibility around 2032, when the rings are at their maximum tilt.

- Other Ring Gaps

Unlike the vast Cassini Division, the Encke Gap is a narrower feature, spanning about 325 kilometers in width. It’s not empty but houses the small moon Pan, which is approximately 28 kilometers in diameter. I can see the Encke Gap with an 8” or larger telescope under ideal conditions, but a 10” or bigger telescope is ideal.

An 8” or larger scope can also resolve the thinner (270 km) Maxwell Gap on an exceptional night with extremely good optics and a keen eye.

- Cloud Belts

Much like its larger neighbor, Jupiter, Saturn exhibits a system of cloud belts visible on its disk, which are organized layers of circulating gases at different latitudes. These belts, however, are not as readily observable as Jupiter’s due to Saturn’s higher, thicker haze of atmospheric methane. Saturn also lacks the dramatic storms Jupiter frequently exhibits, and most of the bands are nearly perfect straight lines.

Nonetheless, with a good-quality telescope, I can discern the alternating pattern of these lighter and darker bands. The most easily visible band is a dark equatorial belt, while subtler bands can be perceived under ideal viewing conditions or with the aid of quality color filters.

Viewing the Moons of Saturn with a Telescope

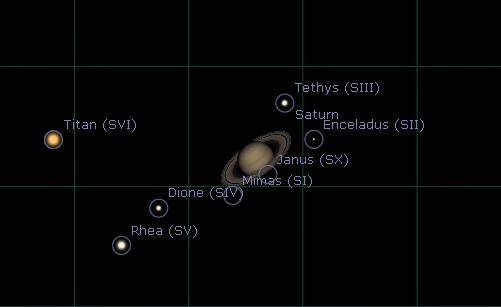

With a modest telescope, we can easily spot the bright pinpoints of light belonging to Saturn’s largest moons. Titan shows a yellowish-orange disk with 10” or larger instruments; the other moons remain pinpoints.

- Titan, being the largest, is easily visible even with small telescopes or high-powered binoculars.

- Iapetus, Rhea, Dione, and Tethys are also discernible under good conditions and with a moderate-sized telescope of 3” or greater aperture, but not with typical hand-held binoculars.

- More difficult to see are the small and close-by Mimas and Enceladus, though a 6-8” telescope usually reveals these for me.

We can notice the positions of these moons changing from night to night as they orbit Saturn, providing a fascinating display of celestial dynamics. By using a smartphone app or a planetarium program like Stellarium you can see where the larger moons will be located in order to pick them out against the star background.

In 2025, the orbits of the larger moons of Saturn and the planet’s rings appear edge-on, thus opening up the possibility of transits like those of Jupiter.

However, most of the moons are too small to resolve with typical amateur telescopes under normal conditions. The exception is, of course, Titan.

Titan will transit across Saturn, often casting a shadow, with 13 of these occurrences visible between May and November 2025, though you’ll need Saturn to be above the horizon at the time of the transits, which may or may not be the case for many of them at your location.

Besides the main circular moons, other Saturnian satellites can be seen by skilled observers with sufficient gear.

- Hyperion tumbling at approximately 15th magnitude is best seen with a 12” or larger telescope.

- Phoebe at approximately magnitude 16 requires at least 16” of aperture along with clear, dark skies.

- During the weeks when Saturn appears edge-on in 2025, there also exists the opportunity to spot a few shepherding moons, such as Janus and Epimetheus, nominally bright enough but physically blocked as well as washed out by the brightness of the rings. All are dimmer than 14th or 15th magnitude and will require a fairly large instrument to be spotted.

Telescope Color Filters for Observing Saturn

I’ve experimented with color filters to observe Saturn. These filters are often marked with numbers based on the Wratten system used for photographic filters. Most of these filters have a negligible effect. Saturn simply doesn’t have a lot of contrasty atmospheric detail, and filters don’t work much on the ring. But they can be of some use.

I think the Baader Contrast Booster or Baader Fringe Killer is indispensable on Saturn if you own a refractor, unless it is extremely well-corrected.

Orange, #21 can help bring out the bands at the poles. Filters #23, red, #29 dark red, #38 dark blue, #56 LIght Green, #58, green, #80a and #82a, blue, can each help to enhance the cloud bands.

Be aware that filters, by nature, absorb light, passing only some wavelengths to your eye. As a result, filters will darken the image. If I’m using a fairly small telescope, say less than 120 mm in aperture, I find that the benefit of certain filters is overshadowed by the darkening of the image.

If you have a set of color filters, experiment to see if you feel they help you. Don’t expect dramatic changes based on the use of filters. Each filter may bring up a particular detail. What I’ve found is that it takes time and practice to make use of filters and see what they reveal.

Conjunctions and Occultations of Saturn

Saturn regularly appears in conjunction with other planets in the night sky due to its alignment with the ecliptic plane. Occasionally, these are close conjunctions where both objects will fit in the same telescopic field of view.

An exceptional one of these occurred when Jupiter and Saturn approached closely in the evening sky in late December 2020. Unfortunately, Saturn doesn’t approach any planets closely for the next couple of years, apart from a Mercury–Saturn–Mars triple conjunction on April 20, 2026. There will also be a few distant passes by Neptune in 2025 and early 2026, when the ringed planet will be about 1 degree away from the ice giant in the sky (and thus visible together at low magnification), and for the most part, stays close by it for most of the year owing to the slow movement and great distance of both giant planets.

In lunar occultations and conjunctions, Saturn frequently appears very close to our Moon or is hidden by it. These events are a thrilling spectacle to witness. Unfortunately, the next set will not occur until 2031.

Saturn also enters conjunction with the Sun approximately once every 378 days between oppositions, when it is unobservable and at its furthest from us. During these periods, known as superior conjunctions, Saturn is on the far side of the Sun from the Earth, rendering it invisible in the Sun’s glare.