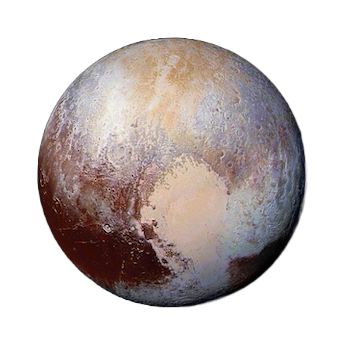

Pluto, located on the fringes of our Solar System in the Kuiper Belt, was once considered the ninth planet from the Sun. Discovered in 1930 by American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, Pluto has since been reclassified as a dwarf planet, but it still remains a fascinating object of study. With a complex surface, intriguing geology, and a diverse collection of moons, Pluto continues to captivate scientists and the public alike. Pluto was the first object to be discovered in the Kuiper Belt, a region of the Solar System beyond the orbit of Neptune that is populated by a vast number of icy bodies.

The hunt for Pluto began in 1906 with a search by Percival Lowell, an American businessman and astronomer who claimed to see canals on Mars that were actually just reflections of blood vessels in his eyeball. Lowell believed that slight perturbations in the orbit of Uranus could not be explained by the gravity of Neptune alone and that another massive body was responsible, which he nicknamed “Planet X”.

We know today that Neptune’s mass was simply underestimated slightly, thanks to data from the Voyager 2 spacecraft, but Lowell was confident in his calculations. Lowell founded the observatory that bears his namesake in Arizona, and a decades-long search began. Lowell believed the planet to be about 7 times the mass of the Earth, or smaller than Neptune, and about 43 AU from the Sun, or 1.5 times the distance Neptune orbits from the Sun.

Lowell died in 1916 and never lived to see the result of his work, though Pluto was actually imaged in other astronomical sky surveys as early as 1909, but no one noticed its movement. A Kansas farm boy named Clyde Tombaugh built his own telescopes in the mid-1920s and sent drawings through them to Lowell Observatory. Impressed, they offered him a job, and Tombaugh began spending hours using a “blink comparator” to look for the ninth planet in photographic plates, carefully lined up with each other and rapidly flashed back and forth to reveal evidence of any objects that moved between the different nights on which the photographs were taken.

Tombaugh found a moving object after less than a year on the job in 1930, and this was believed to be the new Planet X. Though a dissatisfied Tombaugh spent years continuing his search, he discovered many new asteroids, variable stars, and two comets, but no new planets—though he probably could’ve detected the dwarf planet Makemake were it not positioned in the middle of a star cluster at the time of his search.

Pluto was named for the Roman god of the underworld, as suggested by 11-year-old schoolgirl Venetia Burney, who picked it because Pluto was known to be able to render himself invisible. Pluto was automatically a disappointment to its discoverers—six times dimmer than Lowell’s calculations for Planet X and initially thought to be the mass of the Earth. Pluto orbits in a resonance, taking two trips around the Sun every time Neptune makes two, keeping them far away from each other despite crossing orbital paths.

Continually better observations and the discovery of Pluto’s moon Charon allowed its mass and radius to be pinned down accurately, and we know today that Pluto is slightly smaller than our own Moon at 2377 kilometers in diameter and has 17% of the Moon’s mass (or 0.2% of Earth’s). Pluto’s crossing of Neptune’s orbit, combined with the discovery of other objects similar to it in size and orbit, led to its downfall and loss of planetary status. The most prominent of the new dwarf planets, Eris, is roughly the same size as Pluto and actually more massive, briefly considered the tenth planet before the idea was scrapped.

When can I see Pluto from Earth with a Telescope?

Pluto is best viewed around opposition, which occurs in late July for the foreseeable future. It is low in the sky in the constellation Sagittarius, soon to move into Capricornus. However, the dwarf planet is far enough from the Sun in the sky to be observed all the way from around March through October for most stargazers, unless you live very far north, in which case it will barely poke above the horizon in the summer months around its opposition, much like the Sun in wintertime.

What Size Telescope Do I need to see Pluto?

Pluto is gradually getting further from the Sun and getting dimmer as a result. At its perihelion (29.6 AU, or 29.6 times the Earth-Sun distance) in 1989, Pluto was magnitude 13.7 in brightness, but has since retreated from the Sun and is now about half as bright. At magnitude 13.7, Pluto was comparable in brightness to the brightest moons of Uranus and Neptune, but without being near a glare-producing planet, it required less effort to see Pluto with a telescope. It was within the range of telescopes as small as 4 to 5 inches in aperture back then.

Right now, Pluto is hovering at magnitude 14.3–14.4 and losing about 1/10 of a magnitude of brightness every 3 years. It will dip below 15th magnitude in the 2040s and continue to dim until it reaches its aphelion and thus its lowest brightness in the early 2100s. So don’t delay; it’s likely the brightest and easiest to see pluto through a telescope right now than it will probably ever be again for all but the youngest observers.

A 6” or 8” telescope is theoretically powerful enough to glimpse Pluto under dark skies at its current brightness, but few observers are likely to have sufficient dark skies and experience to do so, and it’s not worth torturing yourself to try. Light pollution affects Pluto greatly on account of its dimness. A 10” telescope can show you Pluto fairly conspicuously under dark (Bortle 3 or better) skies, while a larger one is needed in light-polluted environments. A 12” telescope will show you Pluto under Bortle 4-5 skies, while a 14-16” telescope is needed in suburban Bortle 5-6 skies, and places with more light pollution simply won’t allow you to glimpse the faint, icy world no matter how powerful the instrument. These thresholds will all increase as time goes by and Pluto dims.

What does Pluto look like through a telescope?

Pluto through a telescope will appear as a star-like point; no telescope can resolve its disk, which is under 0.1 arc seconds wide; some red giant stars appear larger in the sky, albeit similarly unresolved. The easiest way to confirm you’ve found Pluto is to sketch its position against the background stars and come back a few days or weeks later. You will notice that one “star” has “moved”. Alternatively, familiarizing yourself with the immediate star field around Pluto and using very high magnification to isolate it (as a basically point source, it doesn’t dim at higher magnifications) can also allow you to nail down its position.

Pluto’s large moon Charon is half its size and quite a bit duller, but still technically bright enough to see with 20” or larger instruments; unfortunately, it lies too close to Pluto to possibly resolve as a separate object. Pluto’s other moons—Kerberos, Styx, Hydra, and Nix—are tiny and far too small to observe with amateur telescopes.

Conjunctions & Occultations of Pluto

Conjunctions happen when Pluto appears close to a significant celestial body. Unfortunately, with the exceptions of Uranus (not due for centuries) and Neptune (physically impossible), any body Pluto appears next to will wash it out entirely. The same goes for any occultation of Pluto by the Moon or another planet/dwarf planet. However, Pluto and Charon occasionally occult stars, which is scientifically useful in studying their atmospheres and was instrumental in measuring their diameter before spacecraft were able to visit the icy dwarfs.

Thanks for the info. Very clear and informative.

Can I photograph Pluto through a smaller refractor?

Yes, it’s not terribly faint, but the star field around it is crowded so you’ll need decent sampling