When to See the Galaxy In the Night Sky?

Besides finding a sufficiently dark location, one of the keys to getting the best possible view of the Milky Way from Earth lies in understanding its position and movement across the sky throughout the year.

In particular, the Milky Way is most prominently visible during the solstices, both in summer and winter. Around these times, the densest part of the galaxy reaches its zenith, or highest point, in the sky around midnight.

This is true whether you live in the Northern or Southern Hemisphere, though this article is primarily meant for readers who live in the former or near the equator.

What Do We See When Looking at the Milky Way?

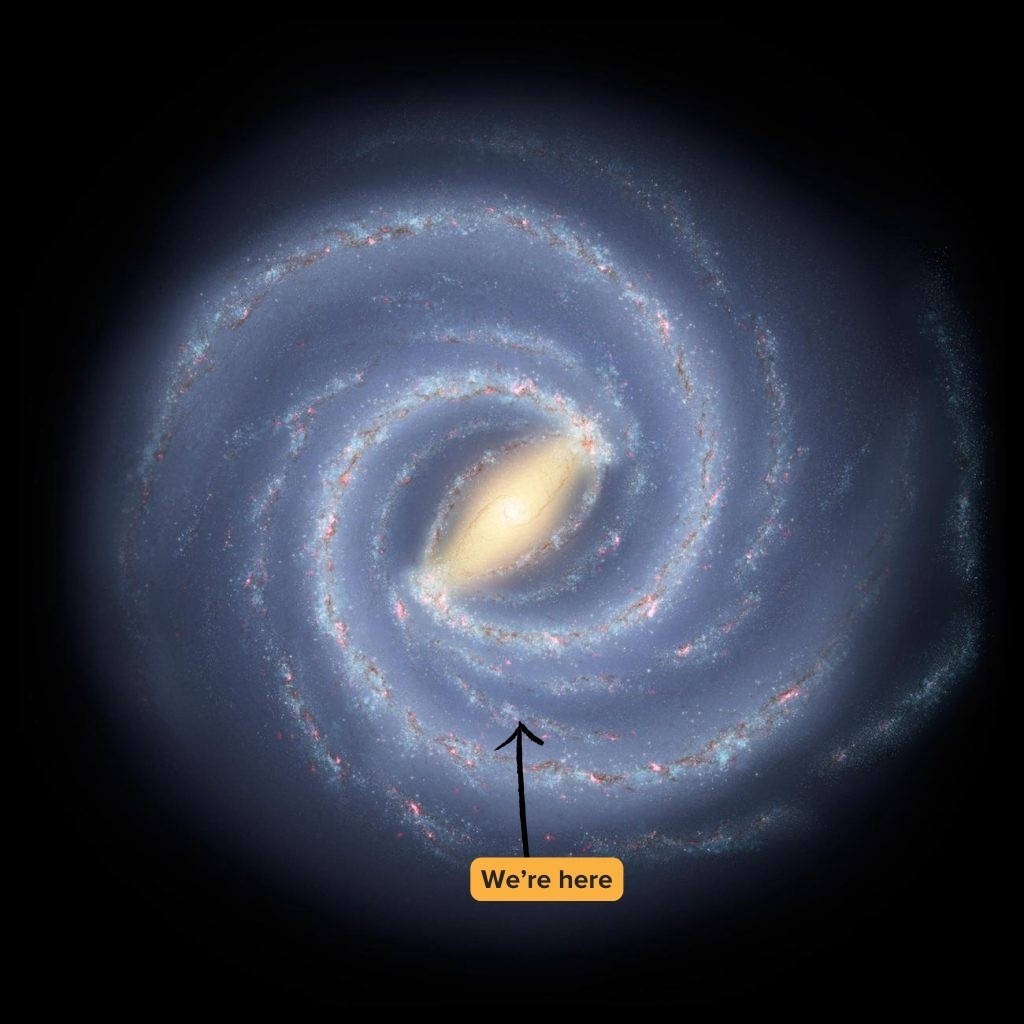

The Milky Way Galaxy is a sprawling, barred spiral galaxy that contains our Solar System, Earth, and countless other celestial bodies. Spanning roughly 100,000 light-years in diameter, it’s home to an estimated 100 billion to 400 billion stars, along with a myriad of planets, nebulae, star clusters, and other cosmic entities.

But when we talk about observing the Milky Way, what are we really referring to?

Skywatcher EQ6R

The dense, milky band of light we see stretching across the night sky is not the entirety of our galaxy. Instead, it’s a view from within, looking outward.

Imagine being inside a vast cosmic disc and looking towards its densest part; the accumulation of distant stars, gas, and dust from our vantage point forms the band we know as the Milky Way.

Why Don’t I Recommend Telescopes for Observing Milky Way Galaxy?

Considering its vastness, I used to assume that tools like telescopes or binoculars would be the best way to observe the Milky Way when I started out. However, this isn’t necessarily the case.

The Milky Way’s appearance in our sky is broad and expansive, covering a substantial portion of the celestial sphere.

Telescopes and binoculars are designed to magnify and focus on smaller sections of the sky, making them ideal for observing distant galaxies, nebulae, planets, or individual stars and clusters. When we use telescopes to look at the Milky Way, we’ll zoom in on specific regions, missing the broader and magnificent view of the galaxy’s sprawling band.

I’ve learned from my years of experience that naked eye or wide-field astrophotography are the most suitable means for appreciating the full splendor of the Milky Way.

Observing without magnification allows me to take in the expansive, cloud-like stretch of the galaxy and witness its grandeur as a whole, rather than focusing on its individual constituents.

How Dark Does My Sky Need To Be To See It?

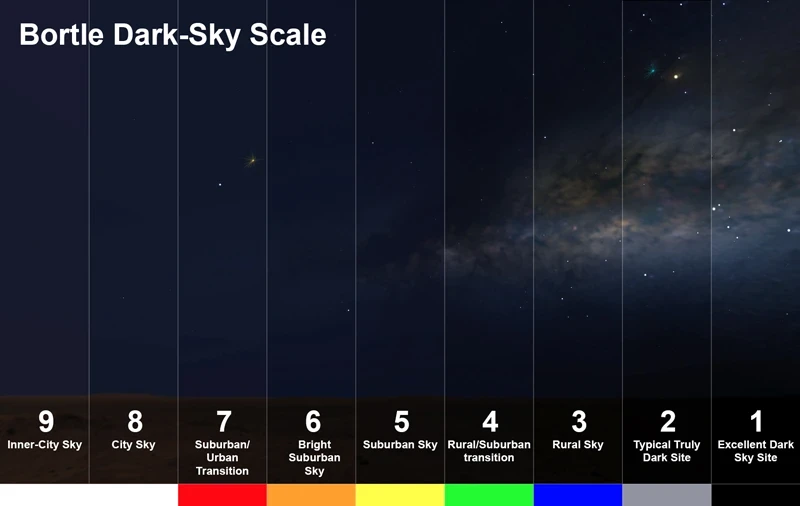

The visibility of the Milky Way in our night sky is intricately tied to the darkness of the sky, typically measured using the Sky Quality Meter (SQM) and the Bortle scale. These scales range in value, with higher SQM values and lower Bortle ratings indicating darker skies.

Our article on light pollution goes into more detail, but here’s a table we’ve borrowed from it showing the NELM, Naked Eye’s Limiting Magnitudes (the magnitude of the faintest stars you can see with your eyes alone), and equivalent Bortle and SQM numbers.

| Light Pollution Map color | Bortle Scale | SQM Reading | NELM (Expert) | NELM (Beginner) |

| Black | 1 | >21.9 | 8.5 | 7 |

| Gray-blue | 2 | 21.6-21.9 | 8.25 | 7 |

| Green-blue | 3 | 21.3-21.7 | 7.5 | 7 |

| Yellow-dark yellow | 4 | 20.8-21.4 | 7 | 6.5 |

| Red-orange | 5 | 19.8-21 | 6.5 | 6 |

| Red-pale red | 6 | 19.5-20 | 6 | 5 |

| Red-pink | 7 | 19-19.5 | 5 | 4 |

The exception to the rule of needing a dark sky is if we are using some sort of electronic assistance, i.e., either wide-field digital photography or a night vision device.

A 1x or 3x magnifier with the correct filters and a typical image intensifier shows the Milky Way under all but the worst possible conditions (bright lights shining directly into the device will damage it). Likewise, astrophotography processing techniques, filters, and the ability to take long exposures allow us to somewhat dodge the effects of light pollution.

However, the view through a night vision device under a dark sky allows me to appreciate far more detail; astrophotography under a dark sky enables a better signal-to-noise ratio and generally allows for a better picture with more detail.

We highly recommend you check your location as well as anywhere you plan on going to stargaze on lightpollutionmap.info or darksitefinder.com. DarkHotels has hotel availability and night sky quality information. Additionally, DarkSky (darksky.org) offers resources for helping with locating and protecting dark skies.

How the Milky Way Look Like in Different Bortle Scale Locations

- Where the SQM is greater than 20.0 mag/arcsec^2 or have an apparent Bortle rating of 6 or higher

The sky is simply too bright to make out the Milky Way. In such conditions, only the brightest celestial objects remain visible.

- With an SQM of around 20.0 and a Bortle scale of 5 to 6

I could only faintly see the brightest sections of the Milky Way near the zenith. At most latitudes, this allows for the bright star cloud around Cygnus to be visible overhead. At lower latitudes (below 35 degrees North), the Sagittarius region around the core of the Milky Way can be glimpsed if positioned high enough.

However, the winter Milky Way remains elusive in these conditions, vanishing amid the light pollution.

In practice, you’re unlikely to be able to see the slightly brighter patches corresponding to the summer Milky Way either, unless you’re used to seeing our galaxy frequently from under a dark sky.

- An SQM of 20.5 (Bortle 5)

This is about the worst sky under which you can still expect to see the Milky Way if you’ve never spotted it before.

The brightest regions of our galaxy mentioned earlier are fairly easy to notice under a Bortle 5 sky, provided the Milky Way is directly overhead, i.e., around the meridian or stretching north to south. Otherwise, the scattering of ambient light by our atmosphere and any additional moisture or pollutants obscures the faint bands of light from view.

Nonetheless, even if the Milky Way itself is largely washed out under these conditions, I can spot M8 and M17 to the south in Sagittarius with the naked eye as fuzzy patches of light a bit smaller than the Moon.

During winter, the Milky Way can be detected, albeit subtly, under a Bortle 5 sky by experienced observers by myself.

More obvious is the view of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31), which is near the northern Milky Way sections that stretch into Cassiopeia and Perseus. Andromeda appears as a hazy glow to the naked eye under a Bortle 5 sky, visible despite being over 2 million light-years away. Binoculars and telescopes reveal M31 to be a spectacular sight.

- Progressing to an SQM of 21.0 (Bortle 4)

The Milky Way starts to truly shine, presenting itself as an unbroken band across the sky, when its central parts are positioned at least 30 degrees or so away from the horizon.

Notable dark bands emerge in areas of Sagittarius and Cygnus.

The winter Milky Way is dotted with a sea of open clusters such as M35 and the Double Cluster, while M31 is readily apparent to even the casual observer.

Nearby, M33, the Triangulum Galaxy, is faintly visible as a hazy patch of light, quite a bit fainter than Andromeda.

You can also spot the planet Uranus and the asteroid Vesta at their brightest as star-like points without optical aid under these conditions.

Many open clusters and nebulae types are obvious to the unaided eye both inside and away from the Milky Way, and you can begin to spot the brightest globulars like M13, Omega Centauri, and M3 as fuzzy “stars” too.

- SQM of 21.6 (Bortle 3)

At an SQM of 21.6 (Bortle 3) or better, the sky becomes a canvas of cosmic artistry and begins to resemble the star-studded awesomeness reflected in the art of Van Gogh or the spectacle of photographs.

The contrasting dark portions of the Milky Way become more pronounced against its glowing backdrop.

Nebulae such as the Lagoon, Swan, and North America Nebula become evident to the naked eye.

Under these conditions, even well-known constellations like Taurus and Sagittarius begin to meld into the sea of stars, making them somewhat challenging to identify.

Also visible is the zodiacal light, a band of interplanetary dust in our Solar System, that can be mistaken for the Milky Way – particularly around the equinoxes. The zodiacal light appears as a band of light emanating from the direction of the setting or rising Sun, along the path of the ecliptic.

Skilled observers may be able to spot the galactic duo of M81/M82 with the unaided eye under a Bortle 3 or better sky, as well as M83 if one is far enough south.

In addition to around a dozen globular clusters, closer to home, Vesta and Uranus are often able to be seen with the naked eye, hiding amidst countless identical-looking 5th- and 6th-magnitude stars.

Occasionally, the dwarf planet Ceres and the asteroid Pallas are also bright enough to be seen under a Bortle 3 or darker sky when they are favorably close to Earth.

A sky sufficiently dark will have clouds that appear truly black unless they are directly overhead or far away above a light dome. This can be problematic since you may not notice the approach of thin clouds or fog until the Milky Way and stars begin to suddenly vanish.

A Bortle 3 sky is all but perfect for the novice astronomer, and through a telescope, the views are nearly as good as under a slightly better sky. However, the Milky Way is noticeably better under a truly pristine night sky, and the views through the eyepiece are sure to be markedly improved too.

- An SQM of 21.8 (Bortle 2)

As we approach the epitome of dark skies, the Milky Way’s radiance intensifies.

Several thousand stars are visible to the naked eye at any time, making the constellations merely clusters of brighter stars against a rich and less colorful backdrop.

M81 and M82 are fairly obvious, as is M33 if you know where to look, while some astronomers have even spotted the planet Neptune – and correspondingly dim 8th-magnitude stars – under these near-perfect conditions.

The dark lanes of the Milky Way streak into Ophiuchus, including around the star Rho Ophiuchi, while almost all of the non-galaxy portion of the Messier catalog of deep-sky objects is visible to the naked eye.

Experienced stargazers may be able to detect Barnard’s Loop wrapping around Orion, and phenomena like airglow and geigenschein become easy to notice. Clouds appear jet black against the night sky.

- An SQM greater than around 21.9 (Bortle 1)

In the darkest skies, the Milky Way can be so luminous that it casts shadows, provided it’s not contending with the brightness of Jupiter or Venus – which themselves cast shadows under these conditions, noticeably brightening the terrain around you.

Under a pristine sky, it almost feels like you’re looking at a black-and-white photograph of our home galaxy, albeit with less contrast between light and dark regions.

The zodiacal light becomes a bit of a nuisance under a Bortle 1 sky, too, as it almost acts like a source of light pollution.

The light of Venus or Jupiter also noticeably brightens the surrounding terrain when they are visible under these conditions.

Effects of Moon Phases in Viewing Milky Way

It’s worth noting that under Bortle 3 conditions or worse, the brilliance of the Milky Way can be entirely washed out by even a fairly thin crescent Moon.

Although the Moon’s presence in darker skies doesn’t render the entire Milky Way invisible, it does compromise its splendor.

If you’re planning a trip to the dark skies to see our home galaxy or stargaze in general, make sure that the Moon either sets before the Milky Way rises or that it rises well after midnight if the Milky Way will already be up around dusk.

Moonlight is just as bad as artificial light pollution when it comes to viewing the Milky Way through both a telescope and with just your eyes.