What’s the most distant object you can see with just your eyes? You might name a local building or point to an aircraft flying overhead. You might even guess the name of a distant star, but an astronomer will give a different answer: the Andromeda Galaxy.

Just how far away is it? The Andromeda Galaxy is a staggering 2.5 million light years away, and yet it’s still one of our nearest galactic neighbors.

In comparison, our Sun (which is actually the nearest star to the Earth) is only 8 light minutes away. Most of the brightest stars in the sky are less than 100 light years away.

The Perfect Time To See Andromeda Galaxy

The galaxy is named after the constellation in which it resides, Andromeda, the princess. Both the constellation and the galaxy are visible from most of the world, but unfortunately not all year round. If you want to see this galaxy for yourself, the best time is during the autumn months, from September to November.

Throughout those months, the constellation and galaxy can be seen rising in the east around mid-evening. (From the northern hemisphere, it can be seen quite high over the southern horizon in early October, around midnight.)

Methods To Find Andromeda Galaxy

There are a number of ways you can find the galaxy. If you have a computerized GoTo telescope and are familiar with how to use it, you could simply instruct it to find the galaxy in the sky. If you live in the suburbs of a large town or city, this might be your only option, as the galaxy is quite faint. (As a result, the light pollution from nearby streetlights may brighten the sky and drown out all but the brightest stars.)

You could also use one of the many free smartphone apps that will identify objects in the night sky. For example, by using an app like Star Walk or SkySafari, you can point your phone toward the sky, and it will identify the stars and constellations for you.

However, it’s much more fun to find a dark location, away from a town or city, and track the galaxy down for yourself. To find it, we’ll first need to find the constellation in which it resides.

By Tracking Big Dipper

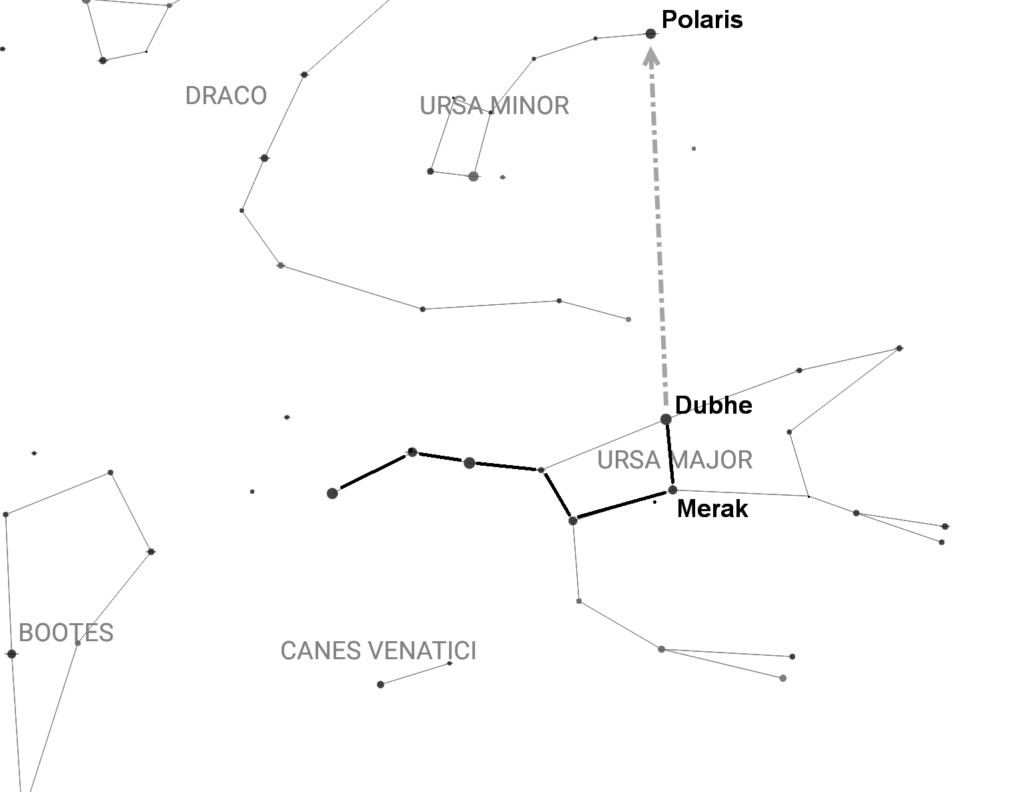

Many people are familiar with the Big Dipper (or the Plough, in the United Kingdom), the seven brightest stars in the constellation of Ursa Major. It’s well known that two of these stars, Merak and Dubhe, point toward the northern pole star, Polaris. We can also use the constellation to help us locate Andromeda.

During the autumn, these stars are very low over the northern horizon, and the further south you live, the lower they will appear. In fact, if you live in the southern United States, you may not see them at all throughout those months.

For this reason, it’s best to go outside at a different time of night and identify the Dipper stars first before attempting to locate Andromeda. In September, try looking toward the north-west once the skies are dark (around 8 pm or 9 pm.) In October and November, the stars will be near their lowest over the northern horizon. During those months, you’ll need to get up early, just before the dawn, to see them rising over the north-east.

This is necessary because we need to use the stars to first locate Polaris. We can then locate another constellation, Cassiopeia, that lies next to Andromeda in the sky.

Once you’ve found the Big Dipper, draw a line through Merak and Dubhe toward Polaris. Keep drawing the line through Polaris and you’ll come to Cassiopeia. If you’re facing north during the autumn months, it’ll appear as a crooked M shape almost overhead.

After Tracking Cassiopeia

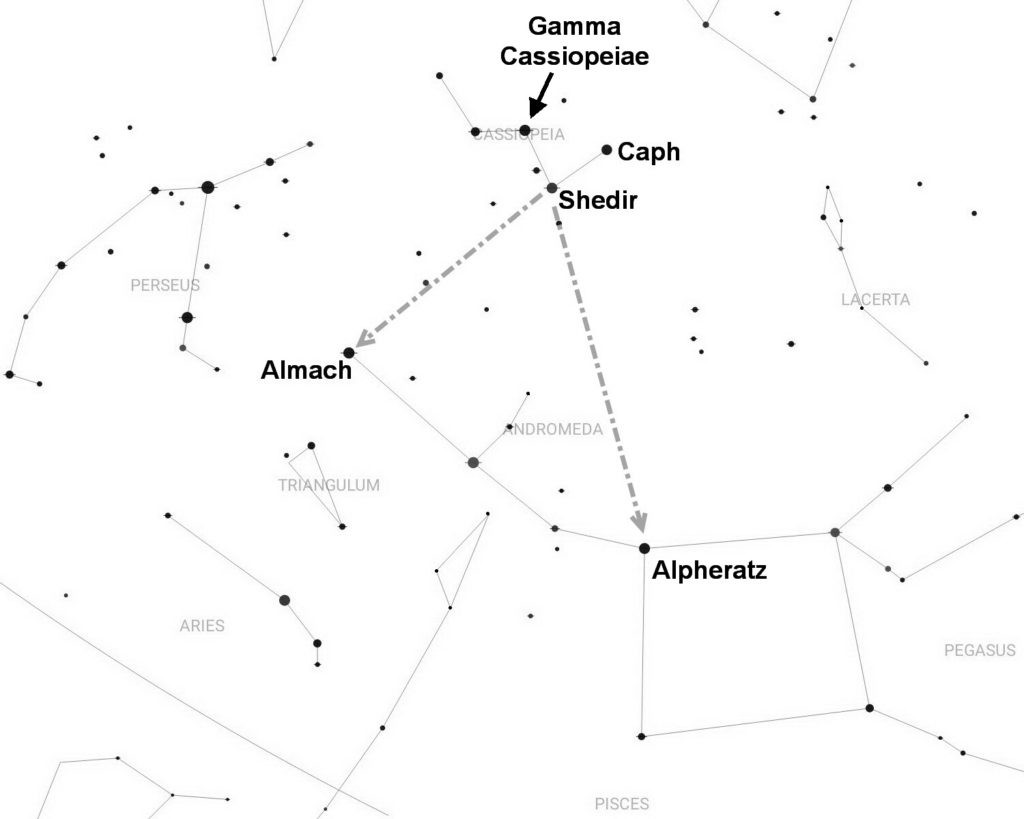

Keeping your eyes on Cassiopeia, turn yourself around so that you’re facing south. The M has now turned upside down and appears as a flattened W. By drawing a slightly curved line from the Big Dipper through Polaris, you’ll come to Caph, the right-most star of the W.

Now look just to the lower left for Shedir, the second brightest star in the constellation. Draw a line through Caph and Shedir to the next bright star, and you’ll come to Almach. This star appears at the end of a line of stars that forms the constellation of Andromeda.

Go back to the middle star in Cassiopeia; this star has no name and is simply known as Gamma. By drawing a line through Gamma and Shedir, you’ll come to the other end of the constellation and the large Square of Pegasus.

The star in the upper-left corner of the square actually belongs to Andromeda and is commonly known as Alpheratz. If you look carefully, you’ll notice that Alpheratz and Almach appear at opposite ends of a slightly curved line of stars. These are the brightest stars in Andromeda.

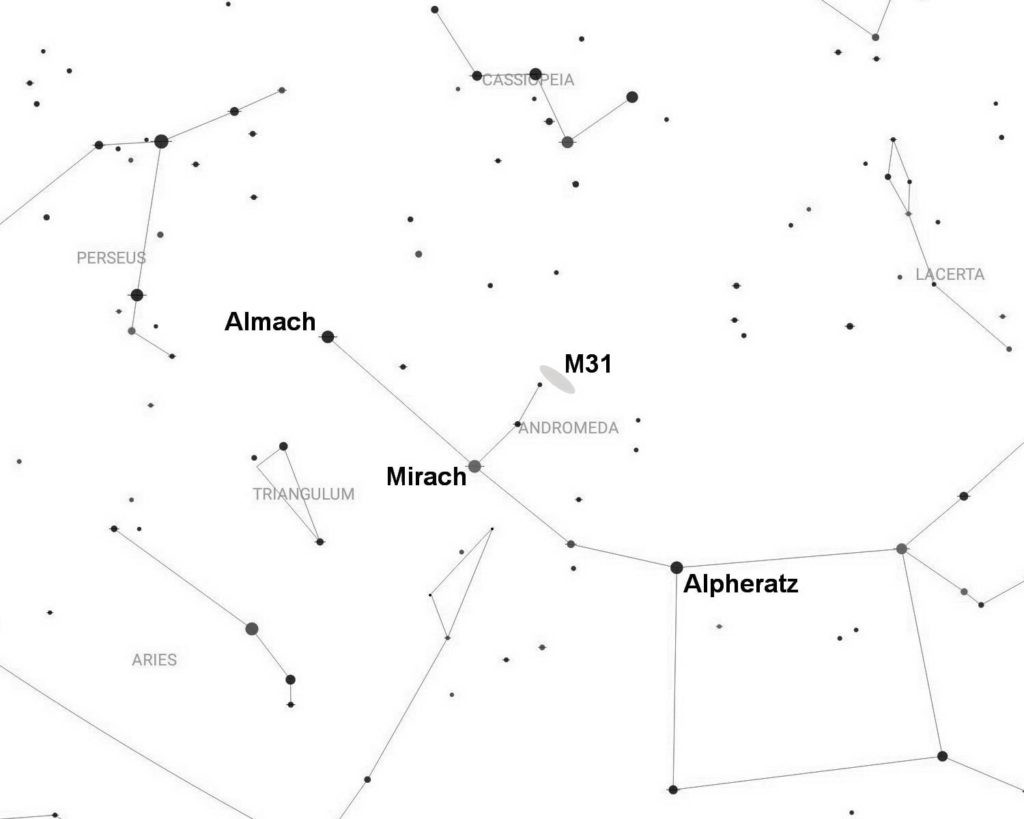

Now count two stars to the left of Alpheratz, the star in the Square of Pegasus, and you’ll come to the reasonably bright star Mirach. (You could simply look one star to the right of Almach, but the gap between the two is quite large. It may be easier to hop away from Alpheratz instead.)

Can you see a fainter star above Mirach? It’s not a particularly bright star, and suburban observers may have difficulty spotting it. (If you have binoculars, it should appear within the same field of view as Mirach.)

This fainter star has no name but has the designation Mu Andromedae. We’re almost there, but we need to hop to another star. Look again, this time above Mu, and you should see an even fainter star. Known as Nu Andromedae, this is the closest naked eye star to the Andromeda Galaxy.

(If you’re observing under suburban skies and have difficulty locating Mu, then Nu will be more challenging. Again, if you have binoculars the pair will appear within the same field of view.)

Observers under clear, dark skies—away from the lights of a town or city—may have already spotted our target. It appears as a tiny, faint gray misty patch in the sky, just slightly above Nu Andromedae. If you live in the suburbs of a town and nearby buildings block out street lighting, you may still be able to see it. Unfortunately, if you live in the suburbs of a city, you may be completely out of luck.

Andromeda Galaxy In a Telescope

Many years ago, long before the lights of our towns and cities polluted our skies, the galaxy was a relatively easy target for astronomers. Indeed, it has been frequently observed and studied for over a thousand years. The Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi made the first recorded observation of the galaxy in 964 AD and described it as a “little cloud.”

Our eyes are only sensitive enough to discern the brightest part of the galaxy. In comparison, photographs reveal its true nature, and it’s an awe inspiring sight. If we could see the galaxy’s full extent with just our eyes it would appear nearly six times larger than the full Moon. Imagine living closer to our Milky Way’s edge and being able to see the Andromeda Galaxy stretching across the sky!

If the view with just your eyes is a little disappointing, use binoculars instead. With just 8×32 binoculars, the galaxy appears as a light gray oval patch in the sky. Try looking at it using averted vision – in other words, center the view on a nearby star (for example, Nu Andromedae) and then try looking at the galaxy as though you’re looking “out of the corner of your eye.” When observed this way, the patch becomes more elongated, with the core appearing about twice as bright as the extended portion.

Telescopes—even a small one—can reveal a lot more, and it’s definitely worth investing the time to uncover the deeper details. At first glance, it appears as a gray and elongated strip with a relatively bright, egg-shaped core. On one long side, the galaxy appears to gradually fade away, while the other long side has a more clearly defined edge.

A moderately small telescope may reveal two slightly darkened bands crossing the core on the sharper side of the galaxy. These two bands are the spiral arms of the galaxy, seen almost edge-on. With a much larger telescope the arms are more easily seen and can appear quite well defined.

Tracking Down M32 and M110 Satellites

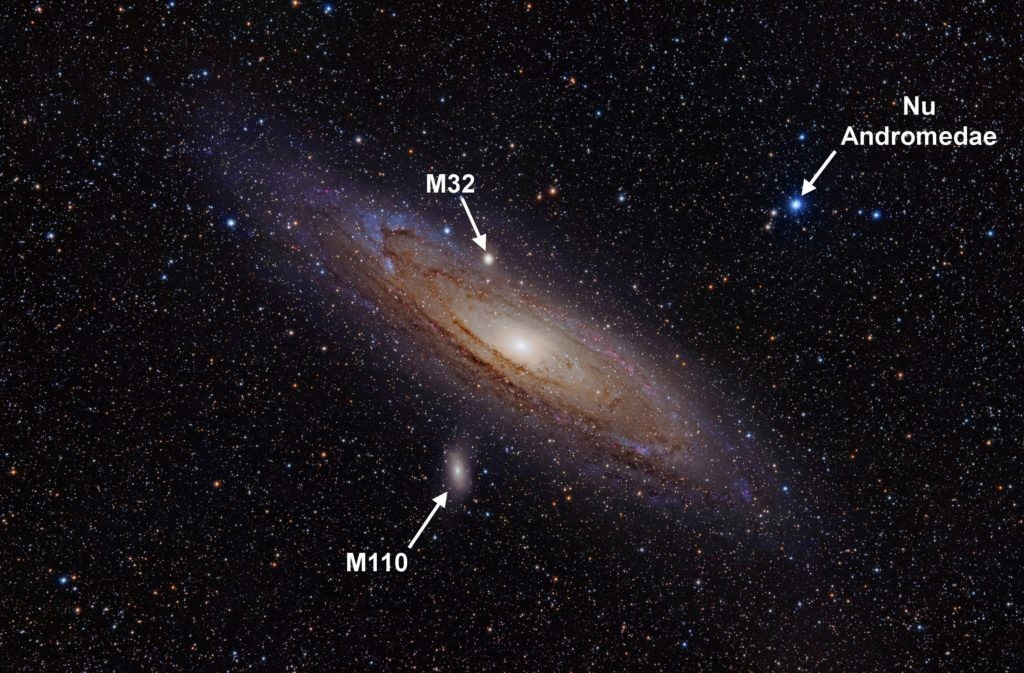

If the arms of the galaxy elude you, try searching for its two tiny satellite galaxies. Astronomers also know the Andromeda Galaxy as Messier 31 (or simply M31); in other words, it was #31 in a catalog of “deep sky objects” that was compiled by the 18th century French astronomer, Charles Messier.

The two satellite galaxies are known as M32 and M110. They are both very small and faint and are difficult to spot with binoculars. Fortunately, both can be seen with a telescope at low power. Of the two, M32 is brighter and easier to track down.

It appears on the long side of the galaxy, which has a gradually fading edge. It may not be obvious at first, but it appears as a very small, nearly circular, hazy patch with a starlike core.

M110 is larger but fainter, so its light is more spread out, making it harder to see. Look for it on the other side of the galaxy from M32 (the side with the more clearly defined edge) and at 1½ times the distance from the core of the Andromeda Galaxy itself. If you can see a small, faint oval patch then you’ve found M110.

Both satellite galaxies appear within the same field of view at low magnification, but neither will show anything of interest. In this instance, the fun comes more from tracking down your targets rather than the splendor of the prizes themselves.

Conclusion – The Significance

Consider this as you stare into the vastness of space: the Andromeda Galaxy is roughly 200,000 light years across and is thought to contain about a trillion stars. It’s more than twice the size of the Milky Way.

The light from the galaxy has taken roughly 2½ million years to reach us. You’re seeing it as it was when our primitive ancestors were first making stone tools in Africa. Perhaps they too once looked up and wondered about that “little cloud” among the stars.

We may not be able to travel through time and space, but the Andromeda Galaxy is a window and a stepping stone into the past. Just as your ancestors once stared unknowingly upon this distant citadel of stars, so you too can do the same.