Among the pantheon of constellations that grace our night sky, Ursa Major stands out not only for its historical and navigational significance but also for its vast celestial repertoire. Even if you’re just getting started in astronomy, you almost certainly already know of Ursa Major’s existence and (hopefully) where to find it in the night sky.

Contents in this article:

Occupying an expansive area of approximately 1280 square degrees, Ursa Major proudly claims the title of the third-largest constellation in the sky, beaten only by the extensive Hydra and Virgo. Rooted deep in myths and legends across various cultures, this constellation, also known as the Great Bear, serves as a beacon for stargazers and astronomers, guiding them through a captivating array of galaxies, nebulae, and star clusters. Ursa Major is a common symbol of both the night sky and the wild lands to the north, which is part of why it was chosen to be depicted on the US state flag of Alaska.

Ursa Major’s recognizability as a constellation, as well as its ties to bear- or hunting-related mythology, is so universal that many historians believe it was likely already rooted deep in the myths and legends of the Indo-European culture around 5,000–7,000 years ago.

In addition to its recognizability, also worthy of mention is Ursa Major’s claim to host one of the most significant regions observed by the Hubble Space Telescope: the Hubble Deep Field. This tiny patch of sky, seemingly vacant to the naked eye, was revealed to be teeming with thousands of distant galaxies upon closer inspection, giving humanity a profound glimpse into the universe’s depth and vastness.

Ursa Major in Mythology

In Greek mythology, one of the most recounted tales is that of Callisto and her son, Arcas. Callisto, a nymph devoted to the goddess Artemis, caught the eye of Zeus, resulting in the birth of Arcas. This union, however, invited the wrath of Hera, Zeus’s wife. In a bout of jealousy, Hera transformed Callisto into a bear. Tragically, years later, Arcas, unaware of his mother’s fate, encountered the bear and nearly slew her. To avert the impending tragedy, Zeus intervened, turning Arcas into a smaller bear and placing them both in the sky. The larger bear, Callisto, became Ursa Major, and Arcas was transformed into Ursa Minor. Callisto is also noteworthy for being the name of Jupiter’s second-largest moon, a rocky world bigger than the planet Mercury.

The Native Americans had their own tales of a starry bear. Several tribes, including the Iroquois and Algonquin, envisioned the three stars of the constellation’s “tail” as three hunters in pursuit of the great bear. According to some versions, the bear is wounded annually, explaining the reddish hue of the autumnal leaves, only to rejuvenate every spring.

Chinese legends, on the other hand, see the primary stars of Ursa Major not as a bear but as part of the “Northern Dipper.” This celestial pattern is deeply tied to Daoist beliefs, symbolizing the balance and cyclical nature of life. And ancient Germanic and Norse tribes believed Ursa Major to be the wagon or chariot of Woden or Odin, forever charging forward into battle as it revolved perpetually high in the sky.

Moving to the Hindu pantheon, Ursa Major is recognized as the “Saptarishi,” or the “seven great sages.” These sages, or “rishis,” are eminent figures in various sacred texts and are said to be forever meditating in the heavens, guiding human spiritual evolution.

Where is Ursa Major in the Sky?

Ursa Major’s vast expanse and distinctive shape make it a conspicuous figure in the northern night sky, serving as an invaluable reference point for celestial navigation. However, to truly appreciate its brilliance and identify its treasures, it helps to understand its position and its neighboring landmarks. The constellation is close to the North Celestial Pole; viewers in the Southern Hemisphere will only see Ursa Major skirting the northern horizon at best.

The most recognizable part of Ursa Major is the Big Dipper, an asterism consisting of seven bright stars. Its “bowl” and “handle” shapes serve as a ready reckoner even for those with a casual interest in the night sky. Notably, the Big Dipper is visible year-round for observers situated at latitudes north of 30 degrees, as Ursa Major is a circumpolar constellation.

How to Locate The Constellation

On a clear night, look northward and identify the four stars forming a somewhat lopsided square. This is the bowl of the Big Dipper. Arcing away from the bowl, you’ll find three more stars that make up the handle. The handle’s curving path is distinct, with the last star appearing almost twice as bright as the other two.

Beyond the Big Dipper, Ursa Major sprawls out. If you’re in a location with minimal light pollution, you’ll discern a series of fainter stars trailing below and ahead of the bowl. These stars complete the figure of the Great Bear.

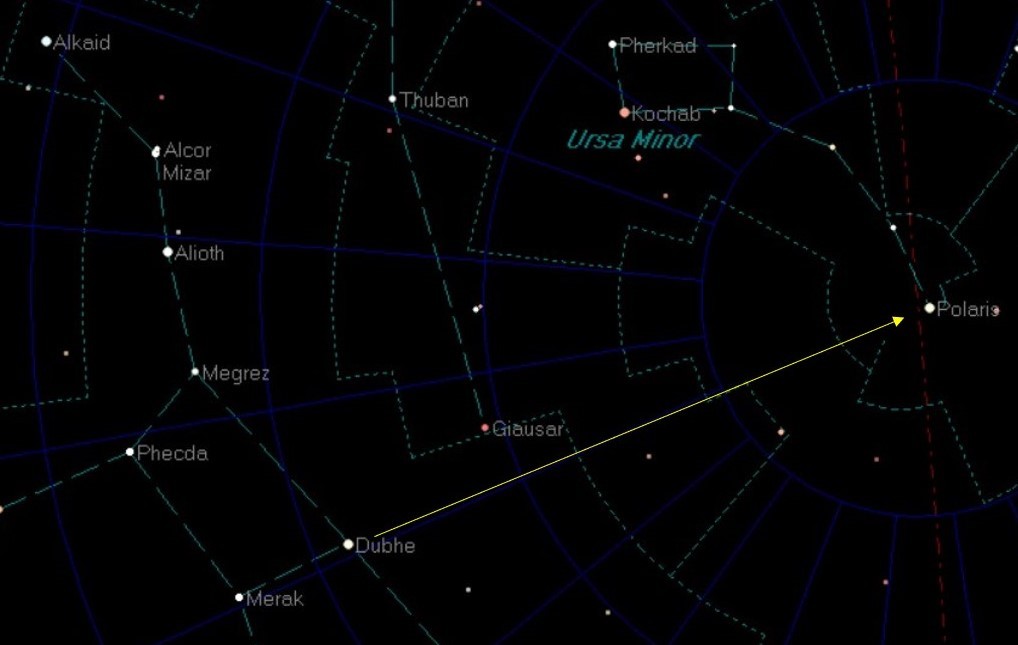

The two stars forming the front edge of the bowl, named Dubhe and Merak, are often termed the “pointer stars”. If you draw a line connecting these two stars and extend it, it points directly towards Polaris, the North Star. Polaris is the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper, or Ursa Minor, Ursa Major’s smaller counterpart.

Things to See in Ursa Major Constellation

Important Stars & Planets

The vast constellation of Ursa Major is more than just a striking pattern in the sky. It’s a veritable tapestry of stars, each with its own unique story and characteristics that contribute to the constellation’s grandeur.

Foremost among these are Dubhe and Merak, the dependable pointer stars that guide many to the North Star, Polaris. Dubhe shines brightly at magnitude 1.8, the second-brightest in the constellation, while Merak is dimmer at magnitude 2.4. While they stand side by side in our sky, the two stars are, in fact, far from one another in space. Dubhe is an older orange giant situated about 123 light-years away, whereas Merak, a somewhat younger white star, is a bit closer at around 79 light-years from us.

Alkaid, or Benetnash, crowns the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle with its distinctive blue hue, blazing at magnitude 1.8. Found about 104 light-years from Earth, this star’s youthful vibrancy sets it apart from its older neighbors, making it the “rebel” of Ursa Major.

Megrez might not boast the brightest glow in the constellation at magnitude 3.3, but it holds a place of prominence as the star that bridges the bowl and handle of the Big Dipper. On the other hand, Phecda, gleaming at the bottom of the bowl, is an energetic young star outshining Megrez at magnitude 2.4. Phecda completes a dizzyingly-fast rotation in less than 24 hours, in stark contrast to the 25 days our Sun takes.

Alioth, another jewel in Ursa Major’s crown, is neither a quiet nor solitary star. As the brightest star in the constellation (albeit barely, at magnitude 1.75), it’s a part of a class of stars known as Ap stars, which have peculiar spectra. These stars have overabundances of some metals and can exhibit rapid oscillations in brightness.

Double & Multiple Stars

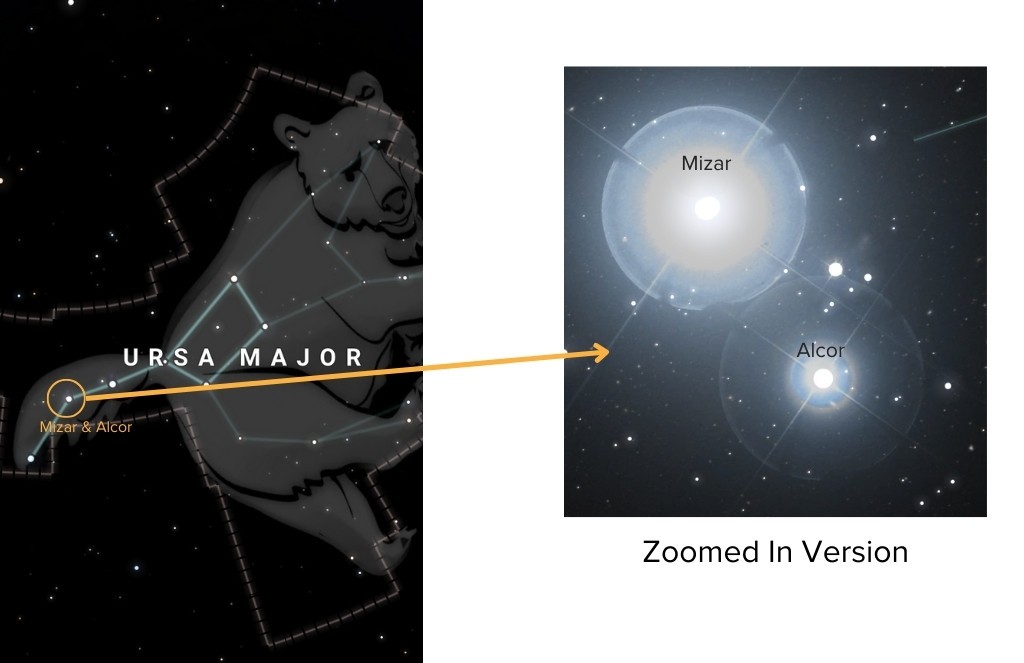

In the curve of the Big Dipper’s handle lies a celestial secret: the stars Mizar and Alcor. Mizar, the brighter of the two at magnitude 2.2, has been used in conjunction with its fainter partner Alcor (apparent magnitude ~4) as a vision test by many ancient civilizations. To the delight of astronomers, Mizar isn’t just a single star but a quadruple star system, while Alcor adds another two as a binary. This means that a point of light that seems simple to the naked eye is a complex family of six stars.

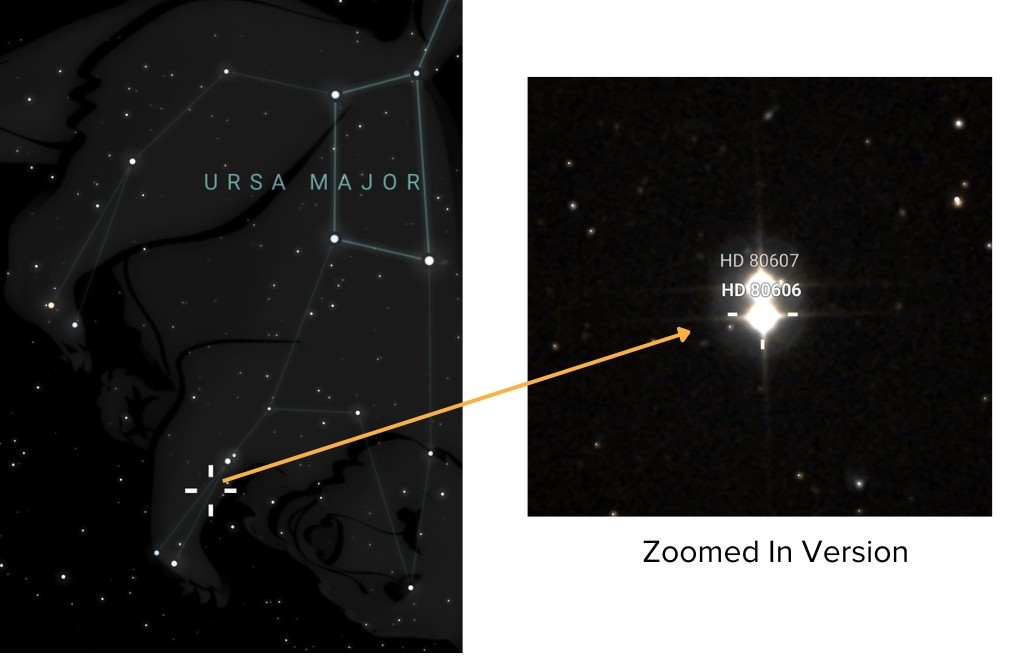

The binary system HD 80606/80607 is a pairing of two Sun-like stars that shine at 9th magnitude and are visible in 50mm binoculars. The pair are 217 light-years away, and are separated by 1,200 astronomical units—that’s 40 times the distance between our Sun and Neptune, corresponding to an angular separation of 20 arc seconds—resolved easily in most telescopes with 30x or greater magnification.

HD 80606 hosts an unusual planet, HD 80606 b, which is a gas giant similar in size to Jupiter but about 4 times the mass. HD 80606 b has the most elongated orbit of any planet known, with an eccentricity of 0.94. The planet approaches its star ten times as close as Mercury does to our Sun, then swings out to about as far as Earth’s orbit, over a period of 111 days. This leads to extreme temperature swings, which can be observed directly from Earth, allowing astronomers to create heat maps of the gas giant’s atmosphere.

Even more oddly, HD 80606 b was discovered via the transit method; it happens to be at the closest point to its star shortly before it swings into our line of sight and blocks out the light of its star for a period of 12 hours. Unfortunately, this monster planet has presumably cleared the way for all other large bodies close to HD 80606 (and thus in its habitable zone), precluding the presence of an Earth-like world – though nearby and similarly Sun-like HD 80607 is not yet known to have any planets, big or small.

Then there’s ξ (Xi) Ursae Majoris, also known as Alula Australis. This binary system appears to consist of two nearly identical yellow-white stars, both of which are magnitude 4.3, with a separation of no more than 3 arc seconds; a 4” or larger telescope, high power, and steady skies are needed to separate them. However, each “star” is in fact yet another binary system, with the twin yellow main stars each hosting dim, ultra-cool red dwarf companion stars hugging close to them.

Lastly, Messier 40 (M40), discovered by Charles Messier in 1764, is a bit of an oddity. A rather ordinary double star, also known as Winnecke 4, was mistakenly cataloged as an open cluster. M40 consists of two yellow-orange stars separated by an arc minute, easily resolved with powerful binoculars or a small telescope. Both members of M40 are around the Sun’s mass, but component A has begun to exhaust its hydrogen fuel and has started inflating into a red giant.

Exoplanets

47 UMa, also known as Chalawan, is another star system in Ursa Major that has been a hotbed for exoplanet discoveries. At an apparent magnitude of 5 and 45 light-years away from us, Chalawan is a bit bigger and brighter than our Sun and hosts three Jupiter-like gas giant planets. Unfortunately, the innermost gas giant lies just outside the star’s habitable zone and is likely to have displaced or prevented any Earth-like planets from forming in the system.

Lalande 21185 (also known as Gliese 411) is a red dwarf and holds the title of being one of the nearest stars to our Sun, sitting just over 8 light-years away. Despite its proximity, it’s not quite visible to the naked eye for most observers; at magnitude 7.5, it is pushing the limits of what is physically possible to spot under pristine conditions. However, any binoculars or telescope will pick up the star. Two rocky planets, b and d, hug close to the star, and a third Neptune-sized planet, c, lies further out. Planet b is a bit too close to Lalande 21185 to be in the star’s habitable zone, while d and c lie well outside it.

Star Clusters

Ursa Major’s distance from the Milky Way in the sky means that it isn’t home to many star clusters or nebulae. When we look at this constellation, we’re looking out away from the populous regions of our galaxy and mostly into intergalactic space.

The Ursa Major Moving Group, also known as Collinder 285, is perhaps the most significant physical grouping of stars in the constellation, though it is not exactly a telescopic or binocular sight. Many of the bright stars of the Big Dipper are believed to be members of this cluster.

Nebulae

As is the case with open star clusters, Ursa Major’s positioning means nebulae are sparse. However, one interesting planetary nebula still lies within the bounds of this constellation.

The Owl Nebula (M97) is one of the more famous planetary nebulae in the night sky. Named for its resemblance to an owl’s face, it’s a dying star’s final breath, captured beautifully in the form of this round, faintly glowing nebula. The central star that expelled the outer gaseous layers is visible with larger telescopes, adding to the nebula’s mystique. A 4” or larger telescope reveals the nebula under all but the worst viewing conditions; a larger aperture, dark skies, and/or a good nebula filter help. Next to M97 lies M108, the Surfboard Galaxy, millions of times further away but remarkably similar in apparent brightness.

Galaxies

Amidst the expanse of Ursa Major lie some of the most iconic galaxies visible from Earth, serving as focal points for both amateur enthusiasts and professional astronomers. The constellation’s seemingly endless realms conceal a myriad of galaxies that reveal much about our universe’s history, structure, and evolution. In addition to the galaxies listed below, Ursa Major’s bordering constellations are home to even more exciting spiral or interacting galaxies like M51 and M63, with the Big Dipper serving as a guide to locating these “faint fuzzies”.

There are so many noteworthy galaxies in Ursa Major that we’ve categorized them below, based on how difficult they are to typically see with a given-sized telescope.

Easy (6” or smaller telescope required) Galaxies

At the heart of Ursa Major’s galaxy-rich territory are M81 (Bode’s Galaxy) and M82 (the Cigar Galaxy). These two galaxies, in close proximity to each other, present a vivid portrait of galactic interaction. M81, with its graceful spiral arms and bright nucleus, contrasts starkly with the irregular and tumultuous appearance of M82, which is undergoing a period of intense starburst activity and appears highly distorted due to gravitational interactions with its neighbor. Accompanying these two giants are several smaller galaxies, making this region a favored target for deep-sky observers and astrophotographers.

Through a telescope, M82 is certainly one of the most spectacular galaxies in the entire night sky. It has the highest apparent surface brightness of any nearby galaxy, meaning it remains surprisingly visible even amidst the washed-out background of a light-polluted sky. Even a 4” telescope shows the slender disk of the galaxy and hints of the dark, twisting hydrogen filaments that cut perpendicularly across it. Larger instruments reveal more subtle details and hints of a bluish tinge to the galaxy’s disk.

M81 is lackluster in appearance with a small telescope or under brightly-lit skies, but with an 8” or greater aperture and sufficiently dark skies, you can see its prominent main dust lane. You may also be able to see hints of M81’s S-shaped spiral arms, but a 10” or 12” telescope is best for the job. 14-16” and larger telescopes begin to show individual H-II regions, or nebulae, in the galaxy’s spiral arms.

Following M81 and M82 in their cosmic vicinity are several notable galaxies. The closest among them is Holmberg IX, an irregular galaxy believed to have formed from the tidal forces of the two larger neighbors. Holmberg IX is visible as a faint patch next to M81 with 12” and bigger telescopes. Also in the vicinity is NGC 3077, which, due to its interactions with the M81 group, showcases peculiar gas structures that intrigue astronomers. These patchy spots of dark dust and gas are visible next to the galaxy’s core on most instruments. NGC 2976, a dwarf spiral galaxy, is a bit further afield and exhibits distorted spiral arms—a likely result of gravitational interactions with M81. Even a 6” telescope shows its mottled appearance.

On the other end of the Big Dipper lies the mesmerizing M101 (the Pinwheel Galaxy). With its well-defined spiral arms dotted with pink nebulous regions and blue clusters of young stars, it is a quintessential face-on spiral galaxy. M101’s face-on nature means it’s very dim and easy to overlook, especially if you have light pollution to contend with. It is also best viewed at very low powers, like Andromeda or M33, rather than the medium to high powers commonly employed for viewing galaxies. M101’s faint spiral arms can be seen in telescopes as small as 6-8”’, while larger instruments bring out the galaxy’s numerous bright H-II star-forming regions and boost the prominence of the arms.

M101 isn’t solitary in its galactic neighborhood. It is accompanied by several satellite galaxies, including NGC 5474, which shows signs of a recent tidal interaction with M101. In long-exposure photos, the galaxy looks like a snail’s shell, and there is evidence that it used to be a spiral before its encounter with the Pinwheel. 6” and larger telescopes reveal NGC 5474’s nucleus, though it may take a considerably greater aperture to view the faint, distorted star-forming region that lies to one side.

The Surfboard Galaxy (M108) is another excellent object not far from the Owl Nebula. It’s a barred spiral galaxy that appears edge-on from our viewpoint. The galaxy’s elongated structure, dotted with knots of star formation and broad dark lanes, resembles a surfboard, giving it its colloquial name. The planetary nebula M97 lies close by, and the two certainly make for a unique pairing in a telescope.

Moderate (8-10” or bigger telescope recommended) Galaxies

Boasting a bright nucleus enveloped by sweeping spiral arms, M109 provides a captivating sight. Its elongated bar structure in the center is a distinct feature. M109 lies extremely close to Phecda, making it easy to locate. However, Phecda’s glare makes observing M109 difficult. A 6” can show the galaxy if your telescope is well-baffled and the sky is good; an 8” or 10” is better suited for the task, however. A 10” or larger telescope begins to reveal the prominent bar as well as the spiral arms of this galaxy. Nearby NGC 3953 is similar in size, brightness, and appearance to M109, and it is possible that Pierre Méchain confused the two galaxies when he first took note of them in 1781.

NGC 2841 is a tightly-wound spiral galaxy near Merak, fairly conspicuous even under light-polluted conditions. NGC 2841 is very similar to the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) in structure, and we view it from a similar angle. Nearly edge-on, it reveals some broad dust lanes with 8” and larger instruments, much like a shrunken version of the Andromeda Galaxy.

NGC 3310, sometimes dubbed the “Pixie Dust Galaxy,” is a starburst galaxy showcasing regions of intense star formation. It is believed that a recent collision or merger with another galaxy sometime in the past 100 million years induced this burst of stellar birth. The galaxy’s bright core and patchy arms, speckled with blue and pink regions (indicating young stars and ionized hydrogen), make it a vibrant target for astrophotographers. A 10” or larger telescope begins to reveal the loose spiral arms of this galaxy.

Another intriguing object in Ursa Major is NGC 2787. This barred lenticular galaxy hosts a ring of dust and gas, a rarity for its type. While lenticular galaxies are usually devoid of such features, NGC 2787 stands out as an exception, making it a fascinating study for those interested in galactic evolution and structure. Through a telescope, it appears as little more than a small smudge, visible in 6” or larger instruments.

NGC 3079 is a barred, edge-on spiral galaxy notable for its “bubble” structure. This galaxy presents a phenomenon where star-forming activities result in the formation of bubbles of superheated gas that rise from the galactic plane, a fascinating display of cosmic dynamics. Through a telescope, NGC 3079 appears to have a star-like center and a broad, slightly bent, elongated disk.

NGC 4013 is a beautiful edge-on spiral galaxy best seen in 8” and larger scopes. Its bright nucleus is gracefully bisected by a pronounced dust lane, a common feature in galaxies seen from this orientation. Next to NGC 4013 lies NGC 3938, a face-on spiral galaxy visible in 6” and larger telescopes. The spiral arms of NGC 3938 will take considerably more aperture to resolve; a 12” or greater instrument is ideal.

NGC 3184, the Little Pinwheel Galaxy, lies less than a degree east of the 3rd magnitude red giant star Mu Ursae Majoris (Tania Australis). While visible in telescopes as small as 6” in aperture, a 12” or larger instrument is best for viewing this face-on spiral.

Hard (12” or larger telescope required)

What sets NGC 4013 apart from many other edge-on spirals is the presence of a mysterious tidal stream. This faint arc of stars, stretching away from the main disk of the galaxy, is a testament to the dynamic and sometimes violent history of galaxies. Tidal streams typically result from gravitational interactions, often when a smaller galaxy is pulled apart by the tidal forces of a larger one. In the case of NGC 4013, this stream hints at a past close encounter or merger event, offering astronomers a rare glimpse into the processes that help shape galaxies over cosmic timescales. The tidal stream of NGC 4013 is an extremely difficult target to spot, likely requiring at least 16-20” of aperture, but it has been observed and sketched by amateurs.

Coincidentally, near NGC 3079 is the Twin Quasar, QSO 0957+561. This quasar, a distant galaxy producing enormous amounts of light as its central black hole devours material, is 9 billion light-years away. Somewhere around halfway between us and the Twin Quasar lies the galaxy YGKOW G1, practically invisible compared to the quasar or NGC 3079 but responsible for distorting our view of the quasar into two images, separated by 6 arc seconds, with its gravity. At a little brighter than 17th magnitude, the Twin Quasar is a worthy target for 20” and larger telescopes.

Meteor Showers

While Ursa Major is primarily known for its distinctive star patterns and deep-sky objects, it also serves as the radiant point for a few meteor showers. These celestial events, though less prominent than the famous Perseids or Geminids, offer observers a chance to witness spectacular, if brief, streaks of light against the backdrop of the Great Bear.

The Ursids, named after Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, are the most notable meteor shower associated with the constellation, though the exact radiant of the shower is in Ursa Minor. Peaking around December 22nd each year, they serve as a celestial treat right before the holidays. Originating from the comet 8P/Tuttle, the Ursids produce about 5–10 meteors per hour under clear, dark skies. What makes the Ursids particularly interesting are their occasional outbursts. In some years, observers have reported rates exceeding 25 meteors per hour.

The other significant meteor shower appearing to originate from Ursa Major is the Alpha Ursa Majorids, peaking around March 22nd each year and produced from the tail of comet C/1992 W1 (Ohshita). While this shower is relatively faint, with only a few meteors per hour, dedicated observers with clear, dark skies might catch a glimpse of these swift streaks of light.