The Decent Optics

The PowerSeeker 60AZ has a 60mm achromatic doublet refractor with a focal length of 700mm and a resulting f/ratio of f/11.7. Almost all achromatic refractors at this focal ratio have slight chromatic aberration, visible as purple halos around the brightest objects such as the moon, planets, and stars. But when I tried the scope, I noticed that the chromatic aberration’s effect wasn’t enough to severely impair its image quality.

The optical quality of the PowerSeeker 60AZ’s objective lens is decent, and that’s one of the few good things I’ll say about the whole telescope.

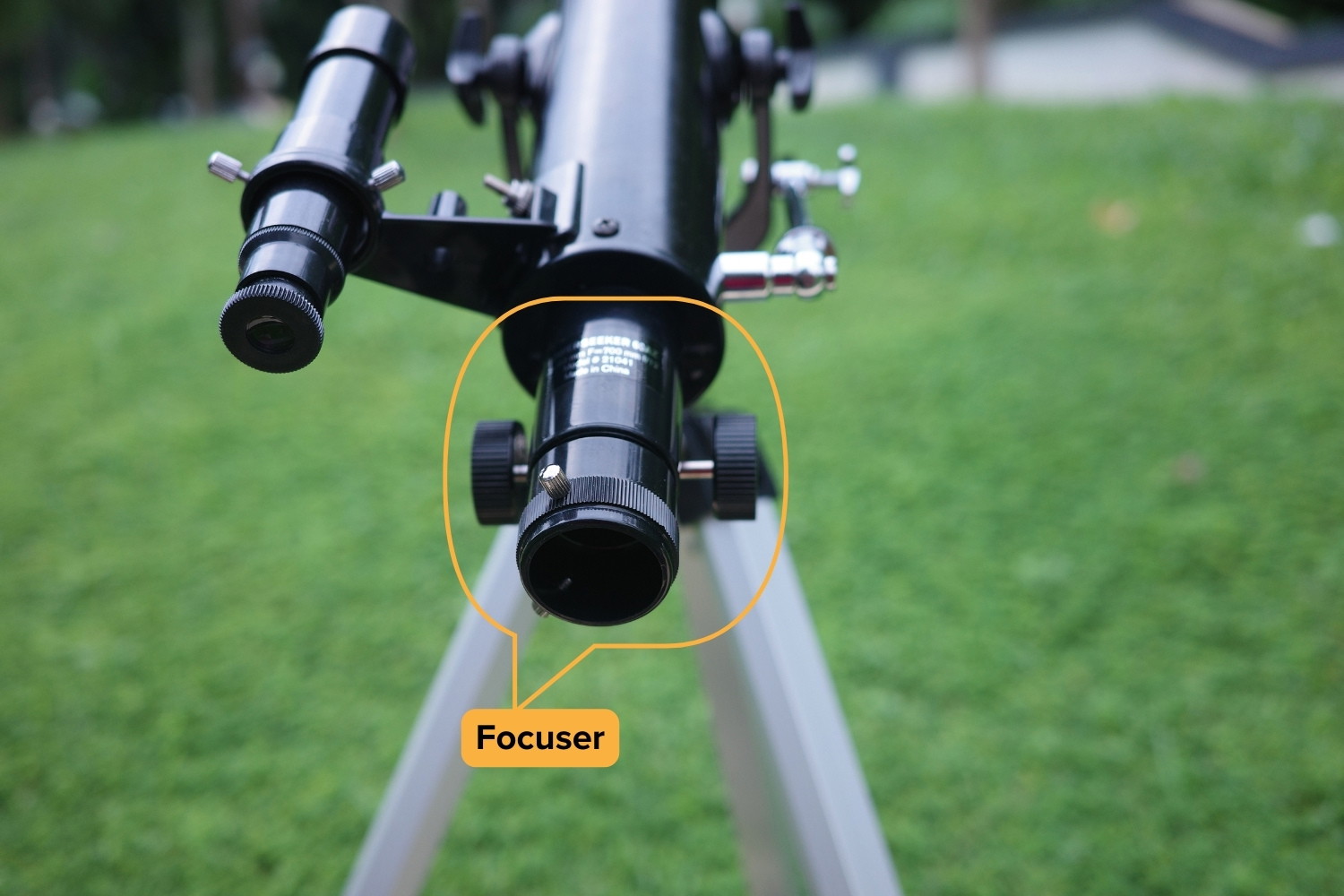

The Plastic Focuser

For a focuser, the PowerSeeker 60AZ uses a plastic 1.25” rack-and-pinion unit.

I’m not saying that a plastic focuser is inherently bad. They are quite common on lower-cost beginner scopes like the PowerSeeker 60AZ. A 1.25” drawtube is also a lot better than the subpar 0.965” focuser drawtube standard of many low-quality telescopes that I’ve tested in the same price range.

But the PowerSeeker 60AZ’s focuser has a lot of wobble and slop when we use it. The drawtube sags and wobbles when I adjust it or move the telescope, which makes the entire view through the eyepiece shift around.

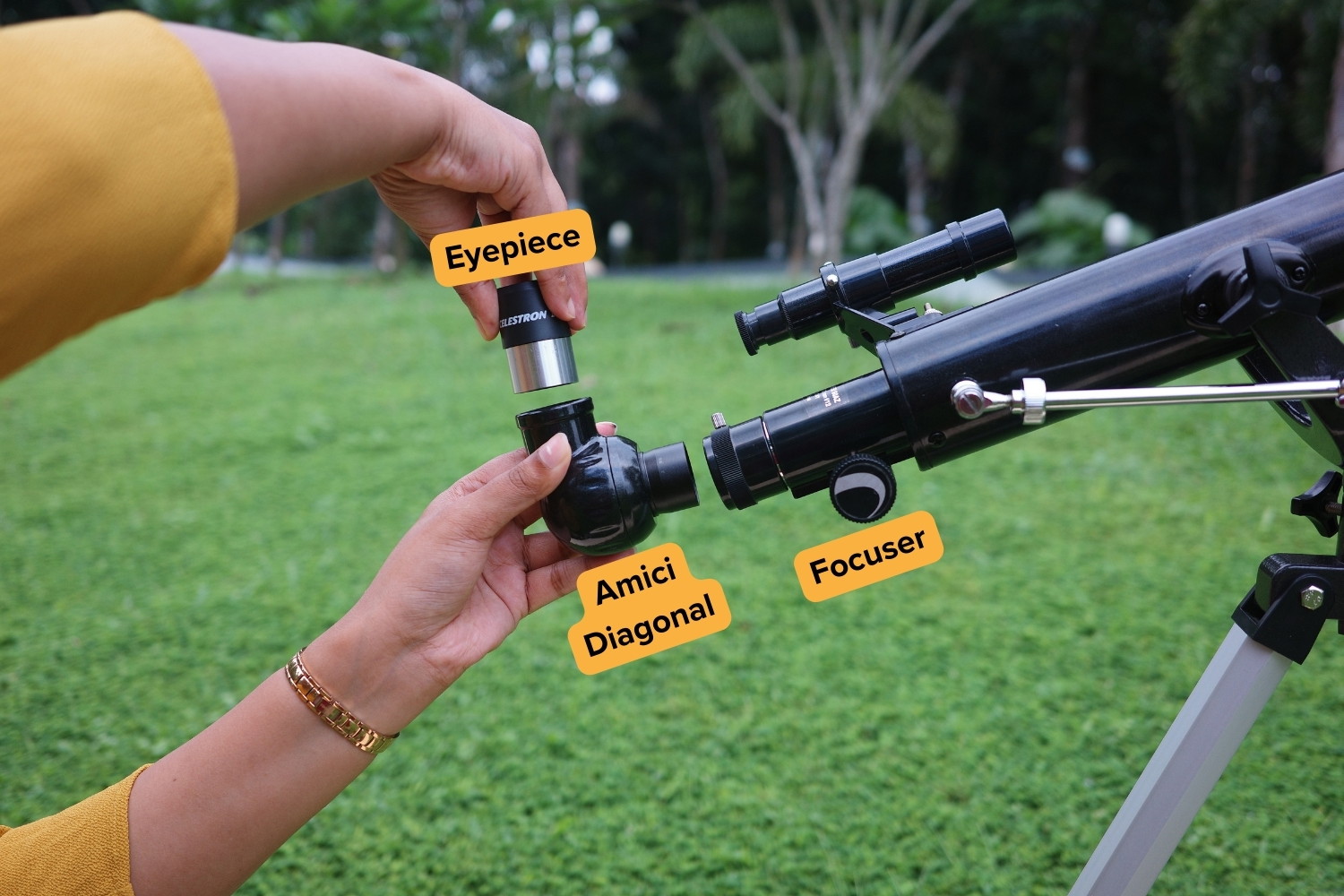

Accessories

The PowerSeeker 60AZ includes a 1.25” erect-image Amici prism diagonal, a 3x Barlow lens, and two 1.25” eyepieces: a 20mm Kellner (35x) and a 4mm Ramsden (175x).

Acceptable Low-Power Eyepiece

The PowerSeeker 60AZ’s included 20mm Kellner eyepiece is of decent quality, with a 50-degree apparent field of view and a fairly sharp image.

It would have been nice to have an even lower power eyepiece than the 20mm, but the included Amici prism diagonal wouldn’t let me use such a wider field eyepiece since its prism is too small.

Many of Celestron’s affordable refractors come with this Amici prism diagonal, which offers the allure of a corrected left-right image but comes with the Faustian bargain of internal reflections, diffraction spikes, and some reduction in overall sharpness.

A good Amici prism would still have the spikes and reflections as a consequence of its design, but its low manufacturing tolerances make the situation worse, and the too-small prism chokes the light coming through the telescope’s already-small objective lens.

The Low-Quality High-Power (4mm) Eyepiece

I’ve found the 4mm Ramsden eyepiece provided with the PowerSeeker 60AZ to be utterly abysmal.

To begin with, 175x magnification when used with the 4mm eyepiece exceeds the usable magnification of any 60mm telescope, providing a dim, hard-to-focus image. And that’s ignoring the reality that the 60AZ hardly has a stable enough mount to handle half that much magnification.

The 4mm Ramsden is also entirely plastic, including the optics, and has an apparent field of view less than 35 degrees across. It requires me to jam my eye into it to look through it at all, and the Ramsden design adds a ton of chromatic aberration on top of the already-blurry views it provides. It is essentially as useful as an extra cap for the back end of the telescope.

The Barlow Lens

The 3x Barlow lens is included with the PowerSeeker telescopes to enable a technical fulfillment of Celestron’s outlandish claims, in this case being able to provide 525x when used with the PowerSeeker 60AZ. Not only is it unlikely that a telescope ten times the size of the 60AZ would be able to use such a magnification, but the Barlow is made of plastic and has a single negative lens that can’t make anything close to a sharp image, even when used with the 20mm Kellner for 105x (which would be the limit of a 60mm telescope on a steady mount).

The Finderscope

For a finder, the PowerSeeker 60AZ comes with a 5×24 unit that uses a stopped-down objective lens made out of a single piece of plastic. The aperture stop brings it to around 10mm, marginally greater than the 7-8mm aperture of our own eyeball.

The eyepiece has a narrow field of view, with rainbows of chromatic aberration visible whenever the finder is pointed at anything bright, though it can at least be easily adjusted for focus by twisting it, and the crosshairs do show up.

The images are blurry, and stars actually appear dimmer through the 5×24 finderscope than through our naked eye. This is despite the whole purpose of a magnifying finder scope being able to show us fainter stars than the unaided eye alone can see.

As bad as it is, the PowerSeeker’s 5×24 finder is at least a better option than attempting to sight through its empty plastic bracket or along the tube.

Aligning the finder is, however, also a nuisance, as the plastic bracket and tiny screws do not stay aligned over time. The finder is prevented from wobbling within the bracket only by a ring of transparent plastic acting as a shim.

The PowerSeeker AZ Mount

The PowerSeeker 60AZ uses a flimsy alt-azimuth fork mount, which pivots up-down and left-right like a photo tripod.

The up-and-down pivot is made up of the two knobs that hold the telescope to the mount and a metal rod that can be used for something that looks like fine adjustment but is really just a decorative piece. The azimuth pivot is made up of a screw in a cylindrical shaft and another screw that is used to tighten it.

Fine motion is not possible on either axis of the PowerSeeker 60AZ’s mount, with the altitude motions being particularly wobbly and hard to aim. This is not helped by the tripod, which has extendable aluminum legs.

The tripod is simply too light to be stable, especially with the legs extended, and most of the hardware is fragile plastic, which may even crack during normal use, such as the leg locks. The mount and tripod are so loose that when I try to focus or aim the telescope at 35x, the whole thing shakes.

Should I buy a Used Celestron PowerSeeker 60AZ?

The PowerSeeker 60AZ is a terrible telescope, and the only thing of value might be the included 20mm Kellner eyepiece if you can get one of these scopes for free. Otherwise, don’t bother.

Alternative Recommendations

The PowerSeeker 60AZ is a pretty awful choice for a beginner telescope.

If your budget is under $100 USD, your only option is a Celestron FirstScope (not much of an improvement, really) or a pair of 50- or 60-mm astronomy binoculars, which are great for deep-sky views but won’t do much for the Moon and planets.

If your budget is more than $100 USD, you can choose from a number of good telescopes other than the PowerSeeker 60AZ.

Under $200

- The Zhumell Z100/Orion SkyScanner 100 has a stable, simple and easy-to-aim tabletop Dobsonian mount, as well significantly more light-collecting and resolving power than the PowerSeeker 60AZ, with a pair of quality eyepieces and an easy-to-use red dot finder included too.

- The SarBlue Mak60 w/Tabletop Dobsonian Mount has similar specs and optical performance to the PowerSeeker 60AZ but is far steadier and more compact, though it does lack much in the way of deep-sky viewing capabilities and only includes one eyepiece.

- The Orion SpaceProbe II 76EQ isn’t the best option out there, but its EQ-1 equatorial mount is steadier and offers more fine adjustment than the 60AZ, and the 76mm aperture provides slightly more light gathering and resolving power. You also get a pair of decent Kellner eyepieces and a simple red dot finder for aiming.

What’d I advise you to look for?

In spite of the great difficulty of using it and its lousy overall capabilities, the PowerSeeker 60AZ still shows you a few things, which is why it gets good reviews on Amazon from people who are impressed with the most basic capabilities a telescope can offer.

A good medium- or high-power eyepiece costs half as much as the 60AZ itself and is unlikely to be easy to use with its wobbly mount, so I’m assuming you’re stuck at 35x.

The Moon showed me a lot of detail with the PowerSeeker 60AZ, as with any decent telescope. At only 35x, I’m hardly pushing the resolution capabilities of even a 60mm instrument and am unlikely to even notice the effects of bad seeing. The larger lunar craters and mountain chains, as well as the most prominent ridges, are seen, along with the smooth texture of the lunar maria.

Mercury proved too small to resolve with only 35x. Even at higher powers, I’ve had a hard time seeing its phases with the PowerSeeker 60AZ.

On the other hand, the phases of brilliant Venus are obvious if I’m not too distracted by the enormous glare from its dazzling cloud tops combined with the purple halo of chromatic aberration around the planet.

Many beginners are just excited to see the four large moons of Jupiter with the PowerSeeker 60AZ, a feat that can also be accomplished with a pair of cheaper and infinitely more useful 7x binoculars. But a good telescope with a slightly larger aperture would resolve their disks and shadows during transit, along with Jupiter’s Great Red Spot and various small atmospheric details. The 60AZ at 35x shows me the moons (even the 5×24 finder reveals at least one) and the two main equatorial cloud belts in Jupiter’s atmosphere, though not the Great Red Spot or any signs of transit.

Saturn’s rings are seen at 35x with the PowerSeeker 60AZ. If it had a decent high-power eyepiece, viewing the Cassini Division in the rings and some cloud belts on Saturn would also be possible with the 60AZ if we could hold it steady. Unfortunately, this is not the case. However, I could see planet-sized Titan at a minimum, along with a few other moons—Rhea being the easiest, but slightly dimmer Tethys, Dione, and Iapetus to be seen if I’m lucky.

Uranus and Neptune are indistinguishable from stars with the PowerSeeker 60AZ, and Pluto is far beyond its light-gathering capabilities.

The PowerSeeker 60AZ shows me the brightest and most prominent deep-sky objects, if I can get it pointed at them.

- Open star clusters are really the only thing outside the Solar System of much interest in a 60mm telescope apart from double stars. Many open clusters, such as the Pleiades or Double Cluster, reveal hundreds of individual members, while double stars require more than 35x to split, apart from the most prominent and easy pairings, such as Almach, Albireo, or Cor Caroli.

- Galaxies like Andromeda show up in the eyepiece, but I couldn’t see any detail.

- Globular star clusters remained unresolved, and most planetary nebulae are too small to see at 35x, as well as often too dim. The Orion Nebula (M42) can be seen as a puffy cloud with the Trapezium cluster within, along with the Lagoon (M8), but fine detail and dimmer nebulae are simply beyond the 60AZ’s capabilities.

If you are under light-polluted skies, your views of deep-sky objects will be further impacted, and even open clusters may struggle to stand out thanks to the 60AZ’s miniscule aperture.

Boa noite Zane. Tudo bem?

Infelizmente na inexperiência de iniciante e na ilusão que o Celestron seria umas das melhores marcas adquiri um telescópio 60az.

Percebi descepcionado tudo que você relatou sobre o telescópio.

Desculpe me mas quais oculares devo adquirir para uma melhor experiência com esse equipamento? E se for possível outros acessórios que possa me ajudar. Muito obrigado! Gostaria de ter lido a sua matéria antes da compra.

I personally find that the transparency around trustworthy service is refreshing and builds trust. The updates are frequent and clear.